For Iron Maiden’s 50th anniversary, our Maiden History series goes back in time to the very beginning.

In the summer of 2025 Iron Maiden was on the road in Europe with the first leg of their massive 50th anniversary tour, Run for Your Lives. The tour title was taken from a line in one of Maiden’s biggest hits, 1982’s “Run to the Hills”, and the setlist focused on their first decade of recording in the 1980s. Video technology and animation was taken to a new level in the stage production, and singer Bruce Dickinson acted out the drama of every song with unbridled enthusiasm. Audiences across the continent were among the biggest that Iron Maiden had ever drawn in Europe, a very far cry from the band’s modest beginnings in London, England all of 50 years earlier.

Bassist and band leader Steve Harris must have reflected on the surreal experience of looking out on these massive crowds from the stage after 50 years of building and maintaining his life’s work with Iron Maiden. Speaking to Classic Rock magazine in late 2024, looking ahead to the upcoming anniversary tour, Harris had said, “When you start out as a band, you don’t think further than your first album. You dream about touring the world.” Indeed, Harris had a dream, but he also put in the incredibly hard work over the course of decades that made Iron Maiden the biggest heavy metal band on the planet in the 1980s, kept them going through the lean and challenging 1990s, and ultimately brought them back to the top of the ladder in the 2000s. Iron Maiden in the new millennium would achieve artistic and commercial merit far beyond even their earlier popularity.

Going back 50 years, to the latter half of the 1970s, the origin story of Iron Maiden is first and foremost a tale of Steve Harris’ vision and dedication, his single-minded belief in his own ideas and work ethic. A lot of people would come and go through the history of Iron Maiden, and the ever-changing line-ups of the earliest days was the symptom of Harris’ tireless search for the right people and musicians. As the band slowly coalesced around Harris and guitarist Dave Murray, the band leader’s vision turned into reality. But even before there was a first Iron Maiden, Steve Harris had to take his musical baby steps.

Influence, Gypsy’s Kiss, and Smiler

Stephen Percy Harris was born on 12 March 1956 in Leytonstone, East London. He grew up in a household with three younger sisters and the constant sound of the radio and records that his sisters were dancing to. As Harris would recall to official Iron Maiden biographer Mick Wall, “I suppose it might be one of the reasons why I got into music as well, because there was always music on in the house.” When his parents divorced, the teenage Harris moved in with his grandmother Ada, and the elderly lady was very supportive of musical ambitions.

However, as is well known, Steve Harris’ first love was football. After seeing a West Ham United game at Upton Park when he was nine, Harris got the bug and became a lifelong Hammers fan. “I liked music and drawing,” Harris said many years later. “But football was always number one for me, as a kid.” Playing for the school team and for the amateur side Beaumont Youth, he soon got on a talent scout’s radar and was offered the opportunity to train with West Ham when he was 14. Which led to a life-changing realisation. “It wasn’t really what I wanted to do, which was a shock, in a way,” Harris said, recalling the single-minded dedication to training and playing that would exclude any kind of social life and any other avenues of personal ambition. “I tried to push myself, but I just thought, ‘I don’t really want to do this.’ It was such a shock to realise that.”

A part of the reason why Steve Harris decided to forego his original childhood dream of becoming a professional footballer, was the fact that he had discovered music that went beyond the Beatles and Simon & Garfunkel songs that his sisters listened to. In the early 1970s, hard rock music was entering its progressive phase, what would forever be labelled prog rock, and in this inventive wave of music Harris found bands like Genesis, Jethro Tull and King Crimson. His friend Pete Dayle must take some credit for steering Harris down this path. “Everyone used to spend all their money on football gear,” Harris said. “And he used to spend his money on albums and really good hi-fi stuff.” As the two teens played chess and Subbuteo, Dayle would keep music going in the background. As Harris recalled:

“I’d start hearing some of these albums again and again, and some of it would start to interest me and I’d ask him all about them, and he’d be like, ‘Well, this is a bit of Jethro Tull and that was a bit of Yes.’ It was all early Genesis, Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin. I borrowed a Jethro Tull album, Stand Up, and I think an early Genesis album and a Deep Purple album. They blew me away.”

Listening to the albums over and over at home, Steve Harris would come to realise that music could give him what football ultimately couldn’t, a way to express himself without sacrificing social connections. “And the next step was I immediately wanted to have a go at trying to play this stuff myself,” as he told Maiden biographer Wall. At first, he wanted to play drums, but drums are noisy and take up a lot of space. Harris settled for learning chords on an acoustic guitar, but what he truly wanted to do was to play the bass along with the drums. He traded the acoustic for an electric Fender bass, the same make that he plays to this day, and started making sounds. “Once I got my hands on the bass, something just clicked and I knew I could do it.” Steve Harris started playing the bass in 1973, at 17 years old. After about ten months of learning by playing along with records, Harris asked his friend Dave Smith, a guitar player, to start a band with him in early 1974.

At first this group was called Influence, and they ultimately consisted of Steve Harris on bass, Dave Smith on lead guitar, Tim Nash on rhythm guitar, Bob Verschoyle on vocals, and Paul Sears on drums. Singer Verschoyle would later recall that, “Dave had started writing songs, one of which was called ‘Influence’, but it was pretty basic, more like punk than rock to me. He wrote another one called ‘Heat Crazed Vole’ – such a horrendous title it used to make us laugh.” There was also a song called “Endless Pit”, which contained Harris’ bass riff for the future Iron Maiden song “Innocent Exile”. The band rehearsed at the house of Steve’s maternal grandmother, Ada, who would become their first champion and protector. Drummer Sears would witness the passion of Ada when confronted with complaints about the noise:

“Ada had a run-in with one of the neighbours one time, and the air went blue. I had no idea sweet old ladies knew words like that. She just told him where to go. ‘You f-off,’ she said. ‘These f-ing boys are gonna be famous.’ She was amazing, such a cool old lady, and a huge influence on Steve.”

“Tough as old boots, my nan,” Harris would remember. But only one of these boys was going to be famous in the end. Influence played one concert, a talent contest where they came second, before changing their name to Gypsy’s Kiss, which is Cockney slang for piss. After only a few pub gigs, however, the band split up. “I suppose the others lost interest, or whatever,” Harris said in retrospect. Verschoyle agreed, saying, “The difference between the rest of us and Steve was dedication. Anything he did, he went at it one hundred percent.” Sears remembers the end of Gypsy’s Kiss as being anti-climactic, members leaving one by one. “By the end it was just me and Steve until one day he answered an ad in Melody Maker.”

The ad was placed by the twin brothers Mick and Tony Clee, who needed a bass player for their band Smiler. The Clees were guitarists, and Harris auditioned for them in early 1975 and joined the band. Mick and Tony were six or seven years older than Steve, and Smiler was already an established pub band, which all made for a learning experience that the young Harris appreciated. Learning a set of covers for an hour plus on stage, interspersed with a few Clee originals, he was playing gigs with Smiler within a few weeks. Paul Sears also joined Smiler as drummer, but he would soon leave and be replaced by Doug Sampson. Not long after, the Clee twins decided to bring in a singer, and recruited Dennis Wilcock. Harris got along well with both the new recruits, and Sampson and Wilcock would later be a part of the early Iron Maiden.

The road to that band, Harris’ ultimate creative destiny, became clearer when the bassist started experimenting with writing his own songs. “We did do an early version of ‘Innocent Exile’,” Harris said. “And there was ‘Burning Ambition’,” he added. Both these songs can reasonable be claimed as the earliest Iron Maiden track, written and attempted with a Smiler that was run by the Clees. As Harris kept writing more intricate music that veered far away from Smiler’s preferred pub boogie, the Clee brothers nixed them as being too complex. A fork in the road appeared for Harris, who decided to leave Smiler to pursue what he sensed was a good musical expression that merited time and attention. “So, basically, that was it, and I left to form my own band.”

Harris and his own music

It was in the final few months of 1975 that Steve Harris worked to put together his own band. In what must surely have been an exciting process of focusing seriously on the songs he was now writing by himself, Harris looked for musicians that would fit his vision of creating a hard rock band with both metallic aggression and melodic sensibility. The first line-up of Iron Maiden was formed before the end of the year: Steve Harris (bass), Dave Sullivan (guitar), Terry Rance (guitar), Paul Day (vocals), Ron “Rebel” Matthews (drums).

“Everything was based around the Melody Maker in those days,” Harris would recall to biographer Wall. “It was the one for all the phone numbers for the gigs, and the ads there for the musos in the back.” This first line-up of Iron Maiden came into being through this process of reading each other’s ads or hearing about each other from friends of friends and so on. After passing auditions with Harris, the band members settled down to rehearse the songs that the bass player and songwriter had cooked up. “I knew we’d have to start off doing some covers, just to get a few gigs,” Harris said. “But I already had a few songs written, and that was what it was really all about, as far as I was concerned.” Guitarist Dave Sullivan would later think back to this formative period as a bit of a creative cauldron:

“Generally, if we had an idea, Steve would listen to it, and if he liked it, it was in. To begin with, it was just some carry-over ideas from his previous band – stuff like the ‘Innocent Exile’ riff, which came from Steve’s days in Smiler – and me and Terry would suggest a few things too. I particularly remember that the starting riff to ‘Iron Maiden’ was mine.”

There would be no doubt that this was Steve Harris’ band, but the band leader was far too pragmatic and sensible to let ego get in the way of good ideas. “I played them some of the songs and I told them the sort of stuff I wanted to do,” he said in retrospect. “I won’t say I knew totally what I wanted to do, because I don’t think you ever really know that, but I did have a direction that I wanted it to go in.” The aesthetic direction Harris wanted to pursue, was the area of aggressive hard rock with lots of melody and twin guitar in it, the latter element inspired by Wishbone Ash and Thin Lizzy. To this end, he now got some of the earliest Iron Maiden songs ready: “Iron Maiden”, “Wrathchild”, “Innocent Exile”, “Burning Ambition”, “Prowler”, “Transylvania”, and an early version of “Purgatory” called “Floating”.

The name for the band was somewhat surprisingly decided upon between members of the Harris family around Christmas time 1975. “It just sounded right for the music,” Steve Harris would recall about the mythical medieval torture device, probably never actually used, shaped as an upright coffin with spikes on the inside. “I don’t remember if I thought of it or my mum did, or someone else in my family. But I do remember saying it to my mum, and she went, ‘Oh, that’s good.’” With a proper name worked out, the first Iron Maiden line-up soon got a residency at a pub called Cart and Horses in Stratford in East London, playing their new songs for a fairly appreciative working-class audience every Thursday night throughout much of 1976.

However, even as the band gelled and new songs took shape, Harris had nagging doubts about his guitar department. Judging that Rance and Sullivan were competent rhythm players who also handled the melodic guitar harmonies well, Harris still felt that neither of them could play blistering lead guitar in the way he thought was essential for Maiden: “I was starting to think I’d need another guitarist to do that.” Ideally, Harris would have liked to keep the Rance and Sullivan combo and add a third guitarist to excel at leads, a three-guitar dream team that was still decades away from Maiden’s reality in 1976. But at the same time, a more pressing concern was the vocalist position, where Harris felt that Day didn’t rise to it.

“We did our first 25-odd gigs with Paul Day,” Harris said. “I think all along hoping that he would get better, because he had a great voice, but onstage he just wasn’t confident at all.” In an early example of how conscious Harris was about the importance of the frontman position, beyond the need for a great voice, he decided to change singer. Paul Day would later recall his own unease and discomfort, saying, “I wasn’t an experienced frontman, and that eventually counted against me. They wanted me to be more showbiz, and I didn’t know how.” Iron Maiden went from a good singer with a lack of stage presence, to Dennis Wilcock, formerly of Smiler, who had a lot of stage charisma despite his lesser singing voice.

Wilcock seemed to be a big fan of KISS and Alice Cooper, and he took to the stage with eye make-up and an assortment of masks and props, including a blunt sword that he would run across his mouth before vomiting blood in the style of KISS’ Gene Simmons. As derivative as it was, Wilcock can reasonably be credited for bringing the concept of horror theatrics to Iron Maiden in late 1976, long before their theatrical productions of the 1980s. Harris welcomed this sense of showmanship to Maiden’s early concerts:

“Den wasn’t technically as good a singer as Paul, but he really had the charisma and the fun side down to a T. And whatever you thought about the way he looked, at least he really threw himself into it, and that was important. I wanted to play these pubs and dives we were doing as though we were onstage at the Hammersmith Odeon or something, and Den was really good at that.”

With a frontman better suited to entertaining the audience, Harris could go about upgrading his guitar section. An opportunity to do so presented itself when Dennis Wilcock told him about a guitarist he knew called Dave Murray. But Rance and Sullivan did not take kindly to the suggestion of adding a third guitarist. “I knew not many bands had done that,” Harris said years later. “But the ones that had – like Lynyrd Skynyrd – had done something really good with it.” Sullivan claims that he didn’t mind: “I wasn’t too bothered, but Terry wasn’t too keen.” Not being too bothered isn’t quite a ringing endorsement in any case, and once Dave Murray showed up to audition, Steve Harris knew without a doubt what his guitar priorities would be: “There was no way I was gonna let Dave Murray go. Not only was he a nice bloke, he was just the best guitarist I’d ever worked with.”

The ins and outs of early Iron Maiden

David Michael Murray was born on 23 December 1956 in Edmonton, Middlesex. His father’s family comes from a mixed Irish and Scottish background, explaining the Murray surname, and Dave Murray grew up in the Tottenham district in North London. Football was an early passion, as was supporting Tottenham Hotspur, but at age 15 he drifted away from sports as he discovered music and started to buy records.

Murray’s father retired at an early age due to a debilitating health condition, and his mother worked part-time cleaning jobs, their poor financial condition causing lots of fights at home and a lot of moving around. “We lived all over the East End of London,” Murray would remember. “Some right dodgy areas too, basically because we were so poor.” The young Dave Murray’s mum would take him and his sisters to the Salvation Army depot for weeks at a time when their father’s mood and behaviour got too dark. “I grew this sort of protective shell around myself,” Murray later admitted to biographer Wall. “You had to know how to keep your head down just to survive.” The later success of Iron Maiden is brought into perspective through the words of their longest-serving guitarist Murray:

“The first thing I did when I made some money with the band was I bought my parents a house. I’d always wanted to do that, because of all the poverty they were used to, just to give them back something solid so they wouldn’t have to move around anymore. It was something I’d always dreamed of doing, if I ever made it with my music, and after that part of the dream had come true, I thought that was it. Like, if everything fell apart tomorrow, at least I’d have done that, and that made me feel good.”

The financial success of Iron Maiden was still a long way off as the teenage Dave Murray set about learning the guitar and teamed up with his school friend Adrian Smith to play music. At the age of 15, Murray had heard Jimi Hendrix’ “Voodoo Chile” on the radio, which made him instantly obsessed with rock music and guitar playing. “Meeting Dave and getting to know him was great for me,” Adrian Smith recalled. “Because he was a little bit further down the road than I was, in terms of playing. We used to go ‘round each other’s houses and play and it was great.” Their first band was a Hendrix-inspired trio named Stone Free when they were about 16, where they mainly did Hendrix and T Rex covers.

“But it was always clear that Dave would be off the moment a proper band came along and asked him to play,” Smith asserted. In 1973, Murray joined a soft-rock band called Electric Gas, and the following year he joined the punk and glam band The Secret, with which he recorded a single titled “Café de Dance” [sic] that was released in 1975. He also played alongside singer Dennis Wilcock in a band called Warlock, where he made a lasting impression that Wilcock would bring with him to Steve Harris when he became Maiden’s new singer. And so, in late 1976, Dave Murray finally crossed paths with Steve Harris, and he decided to join Iron Maiden.

“The first time I met Dave Murray was when he came to audition,” Harris stated. And the calm and soft-spoken Murray proceeded to knock out the Iron Maiden boss with his lead guitar playing: “I remember we got him to play on ‘Prowler’, and he just blew us away, totally.” Harris told Sullivan and Rance that they would have to leave the band if they didn’t agree with bringing Murray in. And so was born the second line-up of Iron Maiden, down to one guitar instead of up to three: Steve Harris (bass), Ron “Rebel” Matthews (drums), Dennis Wilcock (vocals), Dave Murray (guitar). The challenges from here on would be many, and not least of them was the hoped-for addition of another guitarist to complement Murray.

By early 1977, guitarist Bob Sawyer (also known as Rob Angelo) was brought into the band. He did not stay for long, but his lasting mark in Maiden history is the fact that he contrived the dismissal of Dave Murray (!) after only a few months of the brilliant guitarist gracing the band. Sawyer seems to have caused a rift between Murray and Wilcock after a less-than-spectacular gig at the Bridge House in Canning Town, London. Murray looks back in regret: “Bob took some things I’d said totally out of context and went to Dennis and said, ‘Oh, Dave’s just said this about you.’ Like, totally misquoted me!”

There had also emerged a bit of a power struggle between Harris and his singer Wilcock at this time. The latter had grown to resent Harris’ domination of the band, and he demanded that they get rid of Murray. Harris reluctantly acquiesced and told Murray he was out of the band after just a very brief stint. Murray was deeply hurt. “Getting the sack from anything is pretty horrible,” Murray said. “But because I believed in it and loved it so much, getting sacked from the band was quite painful.”

While Murray took refuge in the band of his friend Adrian Smith, an outfit called Urchin, Harris took a completely different approach to the next Maiden line-up. Gone were both Murray and Sawyer, as well as drummer Ron “Rebel” Matthews. Instead, Harris hired keyboardist Tony Moore along with Wilcock’s friend Terry Wapram on guitar and Barry “Thunderstick” Purkis on drums. This line-up played only one gig, at the Bridge House in the spring of 1977, before falling apart. The experiment with keyboards were not to Harris’ liking, as Moore himself remembers: “It was obvious then that what I did wasn’t right for them. They needed two guitarists, and there was no room for a synth.” Furthermore, a chemically impaired Purkis had an abysmal gig that night, and he was summarily dismissed. This, however, did not sit well with Wilcock. He had liked the new sound, and particularly the fact that all three new arrivals shared his love for stage make-up and the influence of Alice Cooper and KISS. Wilcock informed Harris that he too would be leaving.

In the aftermath of this mess, Harris decided on a time-out. What he knew was that he needed a drummer he could trust, and he reconnected with his former Smiler partner Doug Sampson, who was pleased to pick up the drumsticks again for Iron Maiden. “He’d always been my first choice,” Harris later insisted. Next on the agenda, Harris knew that he wanted Dave Murray in the band more than anyone else. Harris sought out Murray after an Urchin gig and offered him the Maiden job back. “I just said yes straight away,” remembers Murray. “I didn’t even have to think about it.” He was in the tricky situation of having to leave his friend Adrian’s band to rejoin Steve’s band, but although Adrian Smith felt it was a blow to Urchin, he also understood completely what Murray wanted. “I think his heart was always with Maiden, even after they fired him,” Smith said. “He just genuinely preferred the sort of thing Maiden were into.” It was a given that Dave Murray would be in Iron Maiden if Steve Harris wanted him, and the reconciliation was an easy one, as Harris said: “When he rejoined the band I thought he actually showed a lot of faith in me and the songs, which I thought was brilliant, and I’ve never forgotten that.”

With Sampson and Murray on his team, rehearsing as a three-piece through the summer of 1977, Harris could now take some time to write more songs and keep an eye and an ear out for that elusive component: a frontman and singer. Getting this part of the band right had proved difficult. “There’s always one bloke who can really sing but is useless onstage,” Harris later lamented, “or one who jumps around and is brilliant, really looks the part, but can’t sing for shit.” Harris’ friend Trevor Searle brought up the subject one night in the pub, saying he had a friend who was quite the good singer and also looked the part. Being at the end of his tether, in the autumn of 1977, Harris resigned himself to accepting the suggestion and asked Searle to send his friend along for an audition. The singer in question would be known as Paul Di’Anno, and he would be the voice of Iron Maiden for their first two albums and their first tours across the UK, Europe, the US, and Japan.

The right line-up

Paul Andrews was born on 17 May 1958 in Chingford, Essex. He was the eldest of ten children, and he grew up with his mum after his father died at an early age. School was never a priority for the young Paul, but getting into trouble was, as it would be for practically his entire life. “I know what people say about me,” he would later tell Maiden biographer Wall, “but the thing is, most of it is true, so I can’t complain, really.”

Taking his late father’s Brazilian surname, at least according to his own notoriously sketchy storytelling, Paul Di’Anno got into classic rock music like Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin, but also fresh 1970s punk like The Sex Pistols, The Clash, and The Damned. When he first tried his hand at singing, it was in punk bands. He claimed to have seen Iron Maiden live in 1976 with Paul Day on vocals, and being utterly unimpressed to the point of leaving before Maiden’s set was finished. By late 1977, however, Di’Anno agreed to do an audition for this band, and drummer Doug Sampson later recalled the occasion:

“My first impression of him was that he was very friendly. Very Jack the Lad, you know, but a very likeable bloke, in fact. And he was good. Really good. The sound of his voice, which was sort of gravelly and loud, suited the way we played really well, I thought. So, straight away, I knew.”

Steve Harris was also impressed, later saying that, “I thought he looked great and sounded great.” The band played some cover songs first, notably the track “Dealer” by Deep Purple, which Murray had to teach Harris on the spot. “And fucking hell,” Harris would remember, “did he sound good or what?” They then proceeded to introduce Di’Anno to their own numbers “Iron Maiden” and “Prowler”, and the singer sounded great on those too. Harris lied about having other singers to see, and sent Di’Anno away, but the band’s conclusion was inevitable. “Then Steve came ‘round to my parents’ place,” Di’Anno later said, “the next day, I think it was.” Paul Di’Anno was in.

By the end of 1977, a stable line-up of Iron Maiden had come into being: Steve Harris (bass), Dave Murray (guitar), Doug Sampson (drums), Paul Di’Anno (vocals). As before, the missing piece was that second guitarist to partner Murray, but Maiden could now confidently book gigs as a four-piece. Their first concert with Di’Anno took place at the Ruskin Arms pub in Manor Park, East London. Along with the Bridge House and the Cart and Horses, the Ruskin Arms would become a mythical site of formation in the history of Iron Maiden.

(Please note that Maiden history and chronology pre-1979 is notoriously murky, and that some sources would put the formation of this line-up in late 1978 rather than 1977. To the author it seems strange that Harris would have gone a year and a half without a singer, since the break-up with Wilcock in spring 1977, and equally dubious that Di’Anno would have joined the band just weeks prior to the recording of “The Soundhouse Tapes”, confirmed to have happened on New Year’s Eve 1978.)

The band was now starting to attract a big following in their own part of London, regularly packing out the venues they were playing. Throughout 1978 the buzz around Maiden grew steadily louder, and Harris thought it was time they start extending their reach to other parts of London and hopefully cities beyond. This expansion proved to be a problem, as Harris recalled: “The punk thing was still really happening then, and places like the Marquee just didn’t want to know about any long-haired band they’d never heard of.” He decided that a demo tape of their songs was needed, in order to bargain for more gigs.

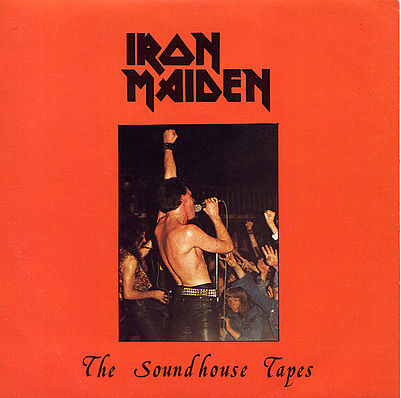

“The Soundhouse Tapes”

What would later become the legendary Iron Maiden EP “The Soundhouse Tapes” was originally known as “The Spaceward Demo”. By late 1978, Iron Maiden had established a great line-up of Harris (bass), Murray (guitar), Sampson (drums) and Di’Anno (vocals). Harris felt ready to expand beyond Maiden’s East London cradle, but he realised that he needed a demo tape to convince people into booking his band for concerts in West London and hopefully other cities throughout the UK. Former singer Dennis Wilcock’s new band V1 had recently recorded a demo at Spaceward Studios in Cambridge. This studio was slightly more expensive than the closer-to-home studios Maiden could get in East London, but Harris thought the sound quality of the V1 demo proved to be worth the extra investment. “We decided that doing it on the cheap was a false economy,” Harris recalled years later. “We knew we’d probably only get one go at it, and we wanted it to sound the best we could.”

Harris managed to take advantage of studio down-time on New Year’s Eve 1978, agreeing a studio fee of 200 GBP plus the services of an engineer, to record four Iron Maiden tracks in a 24-hour session that began on the morning of 31 December. At this point, Maiden were still struggling to find a second guitarist, and the man of the hour was Paul Cairns, nicknamed Mad Mac. Cairns joined Maiden in late 1978 and was the second guitarist for the recording of “The Spaceward Demo” in Cambridge. “I played on all the tracks on ‘The Soundhouse Tapes’ [as the demo would later be known]”, Cairns remembered decades later. “But I never got credited for this.” Indeed, by the time the demo was turned into a vinyl EP in late 1979, Paul Cairns was long gone and not mentioned. In fact, almost 50 years later, Iron Maiden would finally confirm Cairns’ contribution to “The Soundhouse Tapes” in their 2025 official visual history book Infinite Dreams.

For now, on New Year’s Eve in 1978, the five-piece Maiden featuring Cairns recorded four tracks in their first studio experience: “Iron Maiden”, “Invasion”, “Strange World” and “Prowler”. In rock history this is one of the most mythically imbued demo recordings, a quick burst of young energy that committed to analogue tape the melody and aggression that would bring Iron Maiden to the entire world’s attention within a few short years. Harris and Murray originally intended to return to Spaceward a couple of weeks later to polish up and mix the recordings, but by that time the Spaceward engineers had already wiped the master and Maiden were left with the raw cassette copies of their demo. Perhaps this was exactly how it needed to happen for the band to come across to people as exactly what they were.

In Kingsbury in Northwest London there was at this time a discotheque known as The Heavy Metal Soundhouse. The brainchild of rock DJ Neal Kay, the Soundhouse attracted a big crowd to drink and dance around to hard rock and heavy metal music, all in defiance of the in-vogue punk and pop music of the late 1970s. “I kept badgering Geoff Barton at Sounds magazine to come down,” Kay recalled, “because I knew it was unique, and a great story.”

When Barton finally showed up and subsequently published a front-page story about Kay and his Soundhouse in Sounds in the summer of 1978, the term New Wave of British Heavy Metal (NWOBHM) was coined, and the Soundhouse was brought to national and even international attention. Record companies started showing up, and bands began to swamp Neal Kay with their demos in the hope that he would play them for the crowd at the Soundhouse. One of the hopefuls was Steve Harris, who showed up in January 1979 with a newly recorded demo of his band Iron Maiden. As Kay remembers:

“He said, ‘Do me a favour mate. Take this home and give it a listen, will ya?’ I said, ‘Yeah, you and five million others.’ But I took it home, put it on, and it was electrifying. Light years ahead of anything I’d heard. The next night, I played it at the Soundhouse, and everyone went mad.”

“Prowler” would quickly become the most requested track on Kay’s heavy metal nights, and this was reflected in the Soundhouse Chart that Kay compiled regularly for Sounds magazine based on audience requests. Steve Harris would watch dumbstruck as “Prowler” flew all the way to number one in that chart. “I just went down there to get a gig,” Harris recalled. “But he started playing the tracks, and suddenly there were all these requests going on.” Kay knew he was onto something, sniffing that Iron Maiden could be a break-out band from his scene, and he offered Harris a gig at the Soundhouse. “It was absolutely packed,” Harris said, “and we just went down incredible.”

“The Spaceward Demo” did a lot of good for Iron Maiden in terms of building their fanbase and generating media interest and live gigs. But possibly the most important effect of the demo was attracting a key person into their orbit: Rod Smallwood. Some years older than Steve Harris, Smallwood had experience in the music business as both agent and manager, and when he heard the Iron Maiden demo in the spring of 1979, his life changed direction in a way that would greatly benefit Harris’ fledgling band.

Rod and the record deal

Roderick Charles Smallwood was born on 17 February 1950 in Huddersfield, West Yorkshire. A rugby- and cricket-loving Yorkshireman with all the bravado and self-confidence needed to front a challenging project like making Iron Maiden huge, Smallwood enrolled at Cambridge University in 1968 to study architecture, but he gained more valuable experience organising the Trinity College May Ball and booking the bands to perform at it. Making friends and business partners with fellow student Andy Taylor, later to become an essential part of the Maiden organisation, Smallwood sensed that booking and managing rock bands was a meaningful endeavour. The pair would become the main organisers of the May Ball by 1970, but Rod Smallwood was soon becoming restless.

After dropping out of Cambridge in 1971, Smallwood intended to do the proper hippie thing and travel the world for a while. But in his effort to save up money for a trek through Africa and India, he started working as a booking agent for the Gemini agency and quickly got offered a full-time job with the competing MAM agency. Eventually Smallwood started managing the rock band Steve Harley and Cockney Rebel, but he ultimately soured on the experience of dealing with the egocentric and arrogant Harley, to the point where he swore off ever managing a band again.

Smarting from the falling out with Harley and the cold shoulder that his friends and colleagues in the business would give him when he no longer managed the band, Smallwood took off for the US to indulge his love for rugby on a tour of California in the spring of 1979. But just prior to his departure he had heard something good: Iron Maiden. With his complete lack of interest in the reigning punk fashion of the late 1970s, Smallwood was ideally positioned to appreciate the hard rock music of Iron Maiden, and his ears pricked up when a common friend of his and Steve Harris’ named Andy Waller gave him the Maiden demo tape in the spring of 1979. “It was four tracks,” Smallwood remembered. “I was, like, ‘Yeah, this is really happening.’ And it was pretty different from what most new bands I knew were doing at that time, which was mainly punk stuff.”

Upon his return from the US in the summer of 1979, Rod Smallwood decided to call Steve Harris. “I spoke to Steve on the phone and arranged to see a gig.” Smallwood was loathe to venture into the seedy parts of East London, so he offered to get Iron Maiden gigs at two West London pubs: the Windsor Castle and the Swan. The first gig never happened, because Harris had an argument with the pub manager when the latter demanded that Maiden go on stage before their fans from the East End had arrived. The second gig, at the Swan, also nearly didn’t happen when Di’Anno was arrested for carrying a knife and taken into custody at Hammersmith police station. Smallwood suggested the band play anyway, and so he witnessed a three-piece Iron Maiden – Harris, Murray and Sampson – fighting through their set with Harris on less-than-impressive vocals. No matter, thought Smallwood, because: “It was clear they obviously loved playing, loved being onstage, looking the audience right in the eye with total attitude and total self-belief. The charisma onstage just from Steve and Davey was very, very powerful, and I was blown away.”

Smallwood was still not sure that he wanted to become a rock band manager again, but he offered to help Maiden get gigs and a record deal. Eventually, Iron Maiden and Rod Smallwood would sign a management agreement in late 1979, but not before Smallwood had arranged for an impressive recording contract between the band and the major British record company EMI, as well as a properly secure publishing deal with Zomba Music, a company that handles music copyrights and collects money due the band from all possible sources.

Ashley Goodall was a young A&R representative for EMI at the time, A&R meaning artist and repertoire. In charge of seeking out potential new signings for the record label, Goodall had caught the scent of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal. “It quickly became obvious to me that it wasn’t punk bands that were pulling in the crowds, but heavy rock groups,” Goodall would recall decades later. “The first time I saw Maiden was at the Swan in Hammersmith.” Goodall would keep track of Maiden through 1979 and convinced his bosses at EMI to do a compilation album of up-and-coming hard rock and metal bands, which would ultimately become the early 1980 album Metal for Muthas. Iron Maiden would record two tracks for this collection, “Sanctuary” and “Wrathchild”, but Rod Smallwood was simultaneously working out a record deal between Maiden and EMI.

As things were starting to boil for Maiden in the fall of 1979, their concert attendance steadily increasing and Sounds magazine running their first front page and interview feature with the band, Smallwood decided the time was right to flex muscles. He used his contacts in the business to get the band their first headline gig at the very prestigious Marquee Club, and Maiden sold out. It was at this show, on 19 October 1979, that the de facto Maiden manager got several big record companies to attend and witness the spectacle of Iron Maiden and their devoted audience firsthand. Among the companies who sent scouts were EMI, Warner Bros, CBS, and Chrysalis. Iron Maiden now found themselves to be a hot commodity, the tables completely turned from a couple of years earlier when no record company would consider them unless they cut their hair and played punk.

Warner Bros and CBS, however, turned Maiden down. Chrysalis showed a little more interest, and Rod Smallwood had intended to avoid EMI because they had been a part of the Steve Harley debacle that nearly ended the manager’s career. “The fact is, I did still know a lot of people at EMI,” Smallwood said later, “and at the end of the day I knew they’d be able to do the job, and so I thought, ‘I’ve just got to put my own personal reservations behind me and do what’s best for Maiden.’” At the Marquee concert, EMI’s scout, John Darnley, had watched the spectacle at Rod’s side, and Darnley persuaded his A&R boss, Brian Shepherd, to personally visit the Soundhouse for a Maiden concert a couple of weeks later. Shepherd was enthralled by the sheer pandemonium Maiden inspired in the crowd and decided on the spot to offer them a deal. Rod Smallwood then entered into proper negotiations with EMI for an Iron Maiden recording agreement.

“The Soundhouse Tapes” was released at this time, an independent vinyl EP pressing that managed to sell out its original 5000 copies pronto, and thus clearly demonstrated to EMI that Maiden had a serious commercial potential. What Rod Smallwood did now, effectively set up and secured the future of Iron Maiden beyond what just about any other manager would have had the nerve and brains and vision for. In Rod’s own words:

“There are all kinds of deals – deals driven creatively, deals driven by cash, various option deals. We didn’t care about the big advances, but it was a very conscious thing to get them to absolutely commit to making and releasing three albums, come hell or high water. It was a five-album deal, but with the first three albums absolutely firm. It was quite a small advance, and we decided to take most of it for the first album, with the idea that continued revenue from record sales would provide the money to cover the future running costs. So I said, ‘I’ll take 35 000 for the first album, 15 000 for the second, and nothing for the third.’”

The business executive in charge of the negotiations at EMI was Martin Haxby, who would later talk about how the deal that Smallwood wanted was unusual in its long-term vision and the way Rod balanced EMI’s low expectations against the time and effort needed to build Iron Maiden over the course of years. In Haxby’s words:

“Knowing that he would be coming back to us fairly frequently to help finance the various tours they had planned, I think Rod knew the only deal we would agree to would have to be one where the level of up-front cash advances was kept quite low. But where he really scored was in getting the company to agree to making a three-album commitment. That was not something we would have normally agreed to with a new artist.”

Iron Maiden had their record deal, largely thanks to Rod Smallwood. As 1979 drew to a close, the really hard work was about to begin. “The Soundhouse Tapes” was out on mail order, the Maiden tracks for Metal for Muthas were in the can, the EMI deal was signed, and the recording of their debut album was lined up for January 1980.

Final course corrections

Throughout 1979 the quest to find a second guitarist for Iron Maiden continued. Short-lived occupants of the position were Paul Cairns, who had been present for the recording of “The Spaceward Demo” / “The Soundhouse Tapes” in late 1978 before being fired in early summer 1979; Paul Todd, who lasted for only a short while in the late summer of 1979; and then Tony Parsons, who played with the band in the fall of 1979, but ultimately left before the band signed their EMI paperwork as the four-piece Harris-Murray-Sampson-Di’Anno. As the recording of their album approached, Steve Harris decided to hire Dennis Stratton in December 1979.

Dennis Stratton was born on 9 October 1952 in Canning Town, West Ham. He was known around the pubs of London as guitarist and backing singer in the band Remus Down Boulevard, abbreviated to RDB. A few years older than the rest of the band, which Harris thought would come in handy in the form of more experience, Stratton also differed from the others in terms of his musical tastes. “He sort of stuck out,” Harris would admit later. “But we didn’t see that at the time he first came down.” Stratton would stick out enough to last no longer than a year in the band, but he joined at the end of 1979 to take part in a fundamentally important period of recording and touring in 1980.

However, as soon as Stratton had joined, Harris was also having doubts about his friend and drummer Doug Sampson. “We were doing a lot of touring,” Sampson remembers, “just going from gig to gig in the back of a van, and you end up feeding on rubbish, drinking far too much, and then trying to sleep in the back of the van.” The drummer found himself sick most of the time, flus and viruses making him physically unable to perform to the best of his ability. Harris knew that the work would only get harder from that point, and he realised that the band would need a change of drummers, despite the close personal connection he felt with Sampson. Some sleepless nights of ruminating led to Harris’ decision.

Iron Maiden played their final gig with Doug Sampson at the Tower Club in Oldham on 22 December 1979, and the next day Sampson was called in for a meeting with manager Rod Smallwood, who now performed his first of many Maiden exits. “There was only Rod and Steve there to see me, and I kind of knew straight away,” Sampson recalls. “I didn’t argue, I could see their point. The truth is, I don’t think I could have handled it.” It was bound to be painful to leave Iron Maiden right at the cusp of their recording and touring career taking off, but Doug Sampson had done his share of the work to get them there. Dennis Stratton had told the band about a great drummer he knew: Clive Burr, previously of fellow NWOBHM rockers Samson, and now looking for a new job.

Clive Ronald Burr was born on 8 March 1956 in East Ham, Essex. When he picked up the drumsticks, he would develop a powerful style that was partially inspired by Deep Purple’s legendary Ian Paice. A chance meeting between Stratton and Burr in a pub in December 1979 set the drummer on his Maiden course. “I hadn’t seen Clive for years at that point,” Stratton later said. When the guitarist said he’d gotten the Maiden job, the out-of-proper-work Burr asked half-jokingly if they needed a drummer. When Stratton replied in the affirmative, it was soon arranged for Burr to attend an Iron Maiden audition. He impressed with both his playing, his looks, and his demeanour, and on 26 December 1979 he was officially added to the Maiden line-up that would go on to record their debut album.

Sources: Run to the Hills – the Authorised Biography (Mick Wall [1998] 2004), The History of Iron Maiden – Part 1 (DVD, 2004), Killers – the Origins of Iron Maiden 1975-1983 (Neil Daniels, 2014), Loopyworld – the Iron Maiden Years (Steve “Loopy” Newhouse, 2016), Classic Rock Platinum Series & Metal Hammer Present: Iron Maiden (Dave Everley [ed.], 2019), Infinite Dreams: The Official Visual History (2025).

I was there. Yeah, sure, everyone says that…… but I was there at the Queen’s Silver Jubilee Street Party in Teviot St Poplar. I was there at The Tramshed (Woolwich). I was there at Walthamstow’s Assembly Hall. I was there at Imperial College…….. as well as The Cart and Horses, The Plough and Harrow, The Harrow, The Ruskin, The Bandwagon, and most prominently The Bridge House and The Windsor Castle on Harrow Road. I remember that Steve used to sleep in the van (in Steele Road Leytonstone) with all the equipment in case it got nicked. Reason I’m posting this is because I have a unique and very important piece of Iron Maiden memorabilia. I don’t want a penny for it, but I do want either Steve or Dave Murray to have it. Both Steve and Dave will remember me for something I said to Bob Sawyer. I would be very grateful if Steve or Dave could contact me so that I can hand over this small piece of Iron Maiden treasure. Thank you……… Daniel Ayres (Danny) 07956261050 …..fadh@ btinternet.com

Any update, Danny?

Great read, as usual. Nothing extra to say cos I read it weeks ago but looking forward to the next one

Thanks, Jib!