With this first chapter in our study of Maiden History, we take a closer look at how the Maiden sound came into being with the recording of Iron Maiden and Killers. These two albums would lay the foundation for everything that was to follow.

The precise rumble of the bass guitar, the in-your-face banging of loud drums, the chugging rhythms and piercing leads of twin guitars, and the dramatic vocals that soar over the top. This is the sound of classic Iron Maiden. The first time we heard it was on the 1981 Killers album. What came before, the Iron Maiden debut in 1980, was flush with great songs but sonically primitive. What came after, the rest of Maiden’s 1980s, would be the sound of classic metal undisputed.

In reappraising the first two Iron Maiden albums, over 40 years later, one of the most striking things is how Maiden moved from their first attempt, groundbreaking but admittedly flawed, to a second album where they found the sound that their fans know and love. How did that happen?

GETTING STARTED

In late 1978 Iron Maiden recorded one of those demos that become rock legend. In one day the band put down four tracks, three of which would become The Soundhouse Tapes, their first (and strictly limited) vinyl release. No producer, just the band and an engineer rushing against the clock.

It was New Year’s Eve, the studio time was cheap, and an early line-up of Maiden recorded Iron Maiden, Invasion, Prowler, and also the ballad Strange World that would not be included on the original EP release in November 1979.

The decidedly unproduced 7” EP The Soundhouse Tapes was the result of Maiden’s first experience in a recording studio, and was released to fans through mail order in late 1979.

Maiden’s popular live gigs and the demo that turned into The Soundhouse Tapes made enough noise for EMI to sign the band. The label and the fans demanded a debut album, and for that effort Maiden would need a producer.

“We were all young and naïve and we didn’t know about producers and what they do, or don’t do, really.“

Steve Harris

Early sessions had been done in late 1979 while drummer Doug Sampson was in the band, with engineer Gary Edwards. The first Maiden producer can still lay claim to one piece, Burning Ambition, which later showed up on the B-side of the Running Free single. But the band was unhappy with the sound that Edwards engineered for them and wanted someone else to work with.

Iron Maiden in 1980, very comfortable on stage but not so comfortable in a studio. Left to right: Dave Murray, Paul Di’Anno, Clive Burr, Steve Harris, Dennis Stratton. Eddie has taken up his permanent position at the back.

Maiden also recorded two tracks in late 1979 for the first Metal For Muthas compilation album that was released in February 1980. The band put down Sanctuary and Wrathchild with the help of EMI’s in-house engineer Neal Harrison, but it is unlikely that band-leading bassist Steve Harris and hard-bargaining manager Rod Smallwood would ever have considered hiring a producer with such close ties to the record company for their own album.

Iron Maiden on the Metal For Muthas tour in early 1980, before the release of their debut album, left to right: Di’Anno, Harris and Stratton.

Who to get? An exploratory attempt at recording a single with The Sweet guitarist Andy Scott was aborted when the would-be-Maiden-producer suggested that Harris use a guitar pick instead of his fingers, and also wanted a guarantee that he would produce the album before the single recording was completed.

None of that would happen. The search continued…

MAKING IRON MAIDEN

In late 1979 Maiden had signed their first record contract, a contract that manager Smallwood made sure was for the long-term: It commited EMI to backing Maiden for at least three albums to be recorded, released and promoted, and it had a built-in option for a further album number four and album number five.

In short, Smallwood had lined up a contract that covered Iron Maiden’s efforts up until 1984’s Powerslave record, if everything went according to plan. They would even be able to renegotiate for better terms after album number three if their position was good, and that album would turn out to be the breakthrough megahit The Number Of The Beast in 1982.

You’d think the record company would be very particular about getting the right producer for such a commitment, but even the EMI leadership at the time can’t necessarily remember why Iron Maiden were put to work with Will Malone. But on the other hand, Maiden had been very clear that this was their show and nobody else’s, as manager Smallwood would later recall: “The record company never had anything to do with the creative vision of Iron Maiden. No one went into the studio, ever. They even kept me out!”

As the new decade knocked, the clock was ticking: A tour was coming up, and the window for recording would close shortly. So the band entered Kingsway Studios in London with Malone in January 1980, just as soon as they had gotten guitarist Dennis Stratton and drummer Clive Burr in to complement the line-up that already comprised Harris, guitarist Dave Murray and singer Paul Di’Anno.

This line-up of Iron Maiden would record the debut album and tour for about nine months: Clive Burr, Steve Harris, Dennis Stratton, Paul Di’Anno and Dave Murray.

The band was initially impressed with the arrangement, since Malone had artists like Black Sabbath and Meat Loaf on his résumé, although it was unclear to them what kind of services he had rendered to such clients.

It doesn’t seem that Malone was much of a hard rock record producer, he appeared to be in the business of conducting and arranging music, and maybe Maiden and Rod should have known? In any case, Maiden were very quickly unimpressed by their producer’s work ethic, as Harris would recall to official Maiden biographer Mick Wall many years later:

“We’d go in there, we’d do a take, then go in and say to him, ‘What do you think, Will?’ And he’d have his fucking feet up on the mixing desk, reading Country Life or whatever, completely mongled out of his head, and he’d look over the top of it and go, ‘Oh, I think you can do better.'”

Steve Harris

In the end, claims Harris, “we could have taken a complete stranger in off the street […] and it would probably have sounded just the same.” Iron Maiden’s reputation for being first and foremost a live band was already crystalizing, and Harris’ wary attitude towards record labels and producers was seemingly justified.

But Maiden’s failure to properly screen Malone before hiring him extended to not properly checking out Kingsway Studios ahead of recording. Roadie and drum tech Steve “Loopy” Newhouse would remember that loading the band’s gear into Kingsway offered the unpleasant surprise that there wasn’t enough room for Clive Burr’s brand-new drum kit in the drum booth. Burr was consequently set up in an unused reception area, complete with TV and coffee machine, and recording could commence.

Steve “Loopy” Newhouse worked as roadie and drum tech for Iron Maiden from 1978 to 1984. He had a stormy relationship with Clive Burr, not to mention Rod Smallwood, but he witnessed the recording of Maiden’s debut album in early 1980.

When Di’Anno looked back on the sessions for Iron Maiden decades later he would recall a confident band, as anyone can hear on the resulting recording, but he would also remember that his own facade started to unravel a little, at least in his own mind:

“We knew that what we had was unique compared to every other band around, and we had spent the previous couple of years playing every shithole in the UK, also some decent venues as well. The only person who might have had any doubts was me. Though I was a cocky frontman, I was all mouth and no trousers, and when I got into the studio I realised I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing.”

Paul Di’Anno

If the lead singer felt that he was in over his head, it certainly didn’t reflect on the recordings that this line-up of Maiden made in the gloom of the 1980 winter.

One can reasonably argue that the sound Maiden presented on their debut album was simply the-band-doing-what-the-band-did. They had performed the songs on tour for years anyway. But this leaves out an obvious issue: Stratton and Burr had barely joined the band, and had certainly not toured around the country with them.

It seems that Stratton and Burr took to Maiden like ducks to water, and that the nucleus of Harris/Murray/Di’Anno had such a strong identity about them that no disinterested producer could fuck it up. Di’Anno would later recall to biographer Wall that, “You could tell he thought he was far too big to be messing around with something like this. I don’t know why he even bothered showing up, most days.”

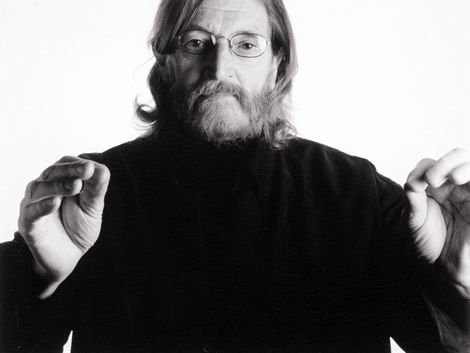

Will Malone, pictured here in recent years, might as well not have turned up for the Iron Maiden sessions, the band says.

But the album got made. And it was good.

Murray gives much credit to his partnership with Stratton, both in terms of sound and performance. Murray played his cherished 1957 Fender Stratocaster while Stratton prefered a Gibson Les Paul, which created a balance of tone that would be important in Maiden’s future music. The guitarists also had a good rapport between them.

“There was a good balance between us, with the Fender and the Gibson. And as far as our parts, we’d sit down and work out harmony bits and stuff. Dennis was quite good. I used to go see him play in bands back in East London and I thought he was stand-out. So it was nice that we got to play together for a bit. And I think there are some great moments on the album.”

Dave Murray

Stratton was the most experienced studio musician in Maiden, and he also found the producer a little too lofty. However, the new Maiden guitarist saw the bright side of the situation: “Will might not have been the greatest producer in the world, but it meant that we could get on with it with the engineers.”

And the engineer on the first Maiden album was one Martin Levan, who went on to have a distinguished career as producer and engineer. “And he was good, thank God,” said Harris. “We actually got some good sounds down.” Levan’s engineering skills facilitated the young and inexperienced Maiden and made the debut album what it is.

Much respected engineer Martin Levan helped Maiden overcome the obstacle of a lofty and disinterested producer.

Harris was never pleased with the production, but he still likes the material today and has a special place in his heart for Phantom Of The Opera, which he says was “indicative of where I wanted to take things with the band. And looking back on it now, I can see it was really a pivotal point in the direction of our music.”

Maiden had arrived. And certain journalists knew it. Malcolm Dome, who wrote many articles on the emerging New Wave Of British Heavy Metal movement at the time, strove to become the voice that nobody could ignore. When covering Maiden’s first Marquee gig in October 1979, he had written: “Maiden received the sort of reception that must send cold shivers down Jimmy Page’s fretboard.” Later, in the spring of 1980, he gave the debut Iron Maiden record a great five-star review in Record Mirror.

Iron Maiden live on stage in 1980, sending shivers up spines and down fretboards. Paul Di’Anno, Steve Harris and Dennis Stratton in the front line.

And Dome was just as sure of the merits of Maiden’s first album many years later, stating in the official Maiden biography that, “I’d say that and the album that followed, Killers, are still my favourite Maiden albums of all time.”

Click here for our review of Iron Maiden!

Maiden had something going for them that would soon push them way ahead of the pack. Their first record might have been the sound of a work in progress, but the live power of the band is obvious in this 1980 video from the Ruskin Arms, available on the official Early Days DVD from 2004:

Indeed, it was Iron Maiden the live band that won over large audiences in 1980. In addition to their own relentless gigging in clubs and theaters around the country, and a prestigious job supporting Judas Priest on their UK tour in March, there was a big prize within Maiden’s reach: The slot as special guests on KISS’ first European visit in four years, the Unmasked tour in the late summer and fall of 1980.

Manager Smallwood had secured the services of booking agent John Jackson, and between them they got EMI to pay for Maiden’s participation in the tour and convinced KISS to go for the young British upstarts as their support act. Coupled with the Priest tour and their performance at the 1980 Reading Festival (second on the bill to headliners UFO), the KISS tour of Europe gave Iron Maiden a profile that was sure to make their British contemporaries green with envy.

At the end of 1980 it would be time to start another record, a follow-up that the band hoped would rectify the underwhelming sonics of their debut. The future and longevity of Iron Maiden, live band extraordinaire, would still depend on their ability to communicate their music skillfully on vinyl.

Dennis Stratton with Gene Simmons during the tour of Europe in 1980. Stratton’s preference for hanging out with KISS and the Maiden crew, rather than his own band, would upset manager Rod Smallwood immensely.

THE RIGHT MAN FOR THE JOB

Even with the positive reception of their debut album, Iron Maiden had yet to find a solid producer. Another false start was made when Maiden’s publishing company Zomba (the office that collects money from around the world whenever Maiden’s copyrighted recordings are sold or played) put them together with Tony Platt. Platt was well known at the time for his engineering career with AC/DC and Foreigner, where he had worked under producer Mutt Lange.

As it turns out, Platt had been directed by Zomba (the money-collecting office, remember?) to get Maiden a hit with the ill-conceived recording of the Skyhooks song Women In Uniform. He thus managed to piss off Harris with some of his commercially inclined production choices, even if the track clearly sounded stronger and better than the first Maiden album in terms of sonics.

Tony Platt at the console in recent years.

Still, Platt had a long-term influence on the Maiden sound through the early trials and tribulations of Bruce Dickinson. The future Maiden singer credits Platt with reshaping his voice and making it “the voice that people recognise today.” Dickinson’s band Samson recorded their third album Shock Tactics (1981) with Tony Platt as producer, and Platt would recall to unauthorized Dickinson biographer Joe Shooman that, “He stopped shouting and he really became an excellent singer.”

Bruce Dickinson (left) with Samson, whose third album was produced by Tony Platt and took the singer to a vocal breakthrough.

Dickinson states in his autobiography that Platt drove him to pitch his voice higher and higher, even uncomfortably so, until “my falsetto screech became almost an irrelevance as my natural voice extended into the back of my eyes.” Platt helped Dickinson find his true voice, but he was not going to be in charge of a Maiden production.

Edwards, Harrison, Scott, Malone, Platt. Five attempts at finding the right man for the job, none of them successful, and Maiden had not even started their second album yet. But unbeknownst to them, on Long Island outside New York City, fate and circumstance was about to bring an end to Maiden’s perpetual producer frustrations.

Martin Birch at the console. By the beginning of the 1980s this man had produced and engineered some of the best records from Deep Purple, Fleetwood Mac, Black Sabbath, Blue Öyster Cult, Whitesnake and Rainbow. He would soon turn his attention to building the Iron Maiden sound.

Record producer Martin Birch was visiting Ritchie Blackmore, guitarist of Rainbow and previously of Deep Purple. It was the early summer of 1980 and Birch had recently produced the seminal Black Sabbath album Heaven And Hell and Blue Öyster Cult’s Cultosauros Erectus. He was already well known as an engineer and producer of Fleetwood Mac and Whitesnake, as well as Blackmore’s Purple and Rainbow.

Blackmore put a record on the turntable, the debut Iron Maiden album, and asked his producer friend, “Why don’t you do them?”

Steve Harris with producer Martin Birch, easily making a completely classic metal album somewhere in the Bahamas in the 1980s.

Birch was disappointed that no one had asked him to do the first album, because, as he said later, it was “exactly the sort of thing I enjoyed, and I could tell that the production didn’t do enough for them on that first album.” But Maiden thought that a producer of Birch’s status wouldn’t even consider coming near young upstarts like them. Steve Harris would later recall that it felt pointless to even consider it, saying, “We all talked about him, but we thought, like, ‘We’re not worthy.'”

Dave Murray would remember the teaming up with Birch as “the real turning point” for Maiden, saying that they “were all big fans of Martin’s work with Deep Purple. We also loved what he did with Black Sabbath on Heaven And Hell, so for Martin to come on board for Killers was fantastic. The whole album was really powerful and atmospheric, and it was Martin Birch who brought that out of us.”

When Birch and Harris finally met up, the producer came clean and told the Maiden chief that he would have loved to do the first album for them. In other words, the question of who would produce the second Maiden album was easily put to rest. They would be produced, engineered and mixed by Martin Birch. Band and producer entered London’s Battery Studios in early December 1980, following a short UK tour that had introduced guitarist Adrian Smith to the fans.

KILLERS AND THE CRITICAL BACKLASH

Birch knew how to make the band feel at ease in the studio. To get the best performances out of the young group, he set them up in the middle of the room and had them perform live. Overdubs would be worked out later, and Birch told them to “just play the songs as you would live, and we’ll work from there.”

“I’d always been interested in getting the natural sound a band produces themselves on stage, and with Maiden I tried to capture that as much as I could. So, to begin with, we just concentrated on capturing their natural sound and put little overdubs on afterwards.”

Martin Birch

It’s interesting to note that this method of putting down album tracks is the very same that Maiden would revert to much later with current producer Kevin Shirley. It’s clear that the live DNA is strong in Maiden, maybe particularly in Harris, and a producer needs to know how to work this into the recording process.

The Maiden line-up that recorded Killers, their first album with producer Martin Birch: Steve Harris, Clive Burr, Paul Di’Anno, Adrian Smith and Dave Murray.

Another major change for the band at the time of recording Killers was obviously the replacement of guitarist Dennis Stratton. After having been in the band less than a year, he fell out with band leader Harris and manager Smallwood, particularly on the KISS tour where he kept his distance from the rest of Maiden and spent much of his time with the crew.

Steve and Rod wanted someone they felt would be a more positive team player. In October 1980 Dennis Stratton was fired and replaced with Adrian Smith, a childhood friend of Murray and the former chief of Maiden’s London rivals Urchin. With Smith and Birch on board, Maiden were finally able to define their sound on record.

Click here to read about Stratton’s and all other exits from Maiden!

It could be argued that the song selection is more impressive on the debut album, but there is no denying that the quintessential Iron Maiden sound came into being with Killers. The fat low-end, the hard-hitting drums, the powerful guitars, and the deliciously judged vocal performances. All of this would become hallmarks of 1980s Iron Maiden records, and it’s very much down to Martin Birch’s skills as producer and engineer. Just compare Killers to Sabbath’s Heaven And Hell, and it’s obvious who is in charge. They both sound like Martin Birch records.

“I’d never worked with a producer who was so totally involved in the whole process. He was a good laugh, but when we were working, he cracked the whip.”

Adrian Smith

Indeed, Birch’s studio discipline soon saw him christened the headmaster, and credited as produced, engineered and bullied by Martin Birch. The already tight band were forced to knuckle down and become “even tighter”, according to Smith.

Dave Murray, Steve Harris and Adrian Smith on the Killers tour in 1981. The relentless studio discipline that producer Martin Birch taught them would pay off in spades. (Photo by Loopyworld.)

But Birch found working with Maiden both enjoyable and easy, saying, “It was pretty obvious from the off that Steve was in charge. Which was good, from my point of view, because me and Steve would agree 99 per cent of the time.” Working with a younger and less blasé band made for a refreshing change for Birch: “I thought, ‘I like this band. I hope we work together again.'”

As it turns out, Birch would soon have Maiden as a full-time job. His choice is easy to understand, as he was doing massive amounts of work in 1980-84 for crazy rockers like Sabbath and Whitesnake. He must have thought that he’d rather stick to the more agreeable and manageable Maiden than be a journeyman in drug-fueled mayhem.

“I was lucky enough to be in the position where I could make that decision.”

Martin Birch

Martin Birch standing in the middle of the men who created the sound of The Number Of The Beast, a year after Killers. Note engineer Nigel Green, second from left, who would return to engineer Maiden in the mid-1990s.

Martin Birch helped give birth to the classic Maiden sound with his work on Killers, and the course for the band’s incredible 1980s era was suddenly clearer. But, ironically, the sonic triumph of Killers was also met with their first critical backlash.

A combination of forces were pitted against Maiden at this point:

1) The inevitable envy in many corners of the music scene, with Maiden’s surprise-hit debut album and high profile tours with Judas Priest and KISS.

2) The fading magic of the once-irresistible NWOBHM scene, fabricated though the slogan was, and the ensuing ego battles between people invested in it.

3) The possibly unavoidable comparisons to the punkish energy of the debut album, which was now being replaced with something more powerful, sophisticated, and ambitious. Journalist Martin Popoff has described this development in memorable terms: “Iron Maiden is wine and downers while Killers is pints at the pub.”

Nevertheless, as a result of this shift Killers got a mauling in their home country. Only Malcolm Dome would give it a positive review in the UK, in Record Mirror, and later said that, “It was almost inevitable that Maiden would start picking up bad reviews. And it’s a shame, because Killers was a great album.”

His sentiment is backed up by the live power of the Killers era Iron Maiden, in this late 1980 London show which is available on the Early Days DVD set:

Click here for a guide to Iron Maiden concert videos!

But whatever the critical backlash, the band wouldn’t care much. Killers sold better than the debut, and Steve Harris actually told biographer Mick Wall many years later that he always preferred it to The Number Of The Beast, saying, “I loved The Number Of The Beast, but I didn’t think it was our best album at the time, and I still don’t.” Given that he says he likes Killers better than the debut, the implication is clear: Harris thought Killers was the best Iron Maiden album until Piece Of Mind (1983).

At this time the band also caught the ears of Samson’s Dickinson, who had been impressed with Maiden’s live shows as far back as 1979. Secretly imagining the great things he could do if he sang for Maiden, Dickinson thought that Killers was much better than the debut album: “When I heard Killers, I was like, ‘This is more like it. This is really gonna do it for them.'”

The recording of Killers at Battery Studios coincided with Samson’s recording of Shock Tactics in the same studio. Dickinson, being a mate of Clive Burr, remembers being invited around for a listen. An inebriated Birch had just finished the mix and played the new Maiden album for Dickinson so loud his ears nearly bled.

The Iron Maiden sound had arrived.

Click here for our review of the Killers album!

THE BIRTH OF LEGENDS

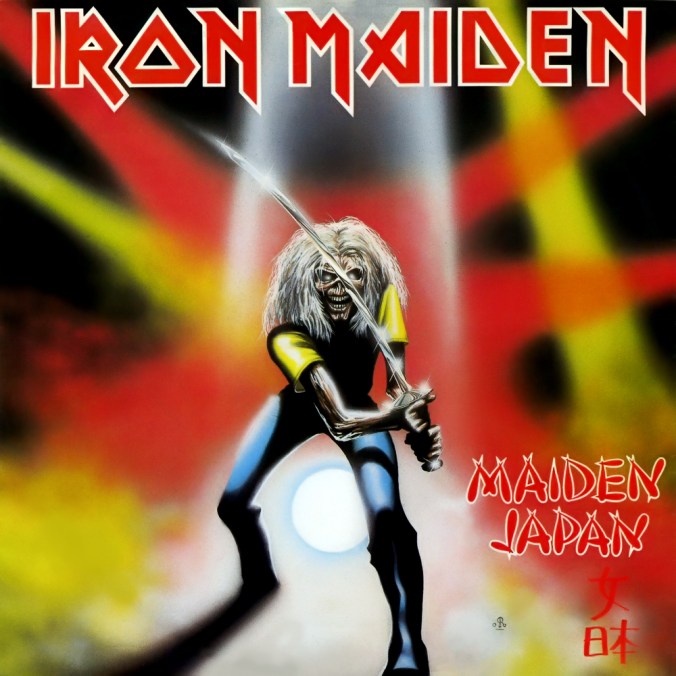

Iron Maiden had toured extensively for their first album throughout 1980, including the Judas Priest and KISS support gigs, and would work even harder in 1981 on the Killer World Tour. This would include their first visit to Japan, where the show on 23 May in Nagoya was recorded for what would become their final Di’Anno release, the Maiden Japan EP. The entire concert was eventually bootlegged:

Recorded and mixed by front-of-house sound engineer Doug Hall and released in September 1981, at exactly the point in time when Maiden fired Di’Anno and hired Dickinson, Maiden Japan is very interesting in the way that the Martin Birch studio discipline seems to have rubbed off on the band’s live performances. Maiden had never sounded as lean and tight as they did on the Killers tour.

The original Derek Riggs artwork for the Maiden Japan EP (top) showed Eddie celebrating the decapitation of Paul Di’Anno. Management quickly commissioned a new version with Eddie wielding a Samurai sword.

As soon as Martin Birch spent a few weeks with Iron Maiden in a recording studio, the birth of the Iron Maiden sound was a fact. The Killers album established many of the sonic Maiden hallmarks that would come to dominate hard rock and heavy metal in the 1980s, and the Maiden Japan EP proved that the producer’s influence also extended to their live performances.

Martin Birch, for his part, turned into a proper legend when he took on the Maiden job. His work before Maiden was impressive, no doubt, but with Maiden he started building a metal icon from the ground up. Over the next decade, he would produce every single Maiden album from The Number Of The Beast to his final work with them in 1992, the Fear Of The Dark album. Suitors would inevitably come forward, and Birch even turned down an offer from Metallica in the mid-1980s.

“They where another band that had been incredibly influenced by both Maiden and Purple, I think, but I was putting so much energy into the Maiden albums, I thought, ‘If I start trying to build up another band in the same way, I won’t be able to give either of them 100 per cent,’ so I said no.”

Martin Birch

In other words, Maiden found a producer as early as their second album who was able and willing to guide them through the process of capturing their essence on vinyl, and who was also willing to make them his sole priority. Birch would continue to provide essential audio and performance expertise as the band grew out of their formative years and into their mind-blowing classic period:

Dawn of the Classic Era, 1982-83.

Like other crucial pieces, Rod Smallwood just before and Bruce Dickinson right after, Birch’s arrival made a world of difference, and it’s hard to see how Maiden would have had the same impact on rock history without him.

Sources: Run To The Hills: The Authorised Biography of Iron Maiden (Mick Wall, [1998] 2001), The History of Iron Maiden, Part 1: The Early Days (DVD, 2004), Guitar World‘s “Maiden Voyage” (Richard Bienstock, 7 March 2011), Loopyworld: The Iron Maiden Years (Steve “Loopy” Newhouse, 2016), Bruce Dickinson: Maiden Voyage (Joe Shooman, [2007] 2016), What Does This Button Do? (Bruce Dickinson, 2017), Iron Maiden: Album By Album (Martin Popoff, 2018), Metal Hammer‘s “Iron Maiden’s Iron Maiden: The Debut Album That Changed Metal” (Dave Ling, 14 April 2020).