Bruce Dickinson and Nicko McBrain were the missing pieces needed to turn Iron Maiden into a true world-class act. With this second chapter in our study of Maiden History we take a look at the dawn of Maiden’s classic era.

From 1980 to 1983 Iron Maiden‘s sound morphed impressively from the early punkish aggression of their first record, through their transitional second album, to the grandiose and ambitious masterworks that would come to characterise their classic 1980s output.

Two of the most important factors in this evolution were singer Bruce Dickinson and drummer Nicko McBrain, who made their album debuts with Maiden in 1982 and 1983 respectively. This chapter will discuss the history of how they joined Iron Maiden, and argue that the band would never have had their golden age without them. Dickinson and McBrain proved to be performers that could always be relied upon, professionals that could always be trusted.

After carefully building their reputation in Britain and Europe, even having visited Japan and also launched their first bid for North American success, Iron Maiden found themselves at a crossroads in late 1981. Their first two albums, Iron Maiden (1980) and Killers (1981), still stand among the most impressive debut/sophomore duos in rock history, but there was trouble behind the scenes, and sometimes even on stage.

It wasn’t all a walk in the park for Maiden (ouch). Dennis Stratton and Paul Di’Anno, to the right, would be out before the band hit the big-time.

Guitarist Dennis Stratton was fired after the first album and tour, to be replaced by Adrian Smith. At the conclusion of the Killers tour, another line-up change was inevitable: Singer Paul Di’Anno had done his last Maiden gig. While Stratton was a case of mismatching, being older than the rest and antagonising band chief Steve Harris and manager Rod Smallwood with his taste in music and his attitudes in general, Di’Anno was a case of sex and drugs and a lack of trustworthiness.

“HE DIDN’T PUT THINGS RIGHT”

In the spring of 1981 Maiden had to cancel a series of concerts in Germany and Scandinavia because Di’Anno had ostensibly lost his voice. As the band headed out on their first ever tour of the USA and Canada in the summer of ’81, opening for Judas Priest, it would be on the shaky foundation of not trusting their singer.

Di’Anno went for the rock’n’roll lifestyle of booze, drugs and women pretty much 24 hours a day, every day of the week, and his performances suffered greatly from the physical and emotional strain. He also, and inevitably, got increasingly estranged from Harris, who would later say that Di’Anno “was read the riot act, and given the chance to put things right. But he didn’t put things right.”

Touring relentlessly was a cornerstone of Smallwood’s plan for Iron Maiden to conquer America. It became clearer day by day that they would find it hard to progress with Di’Anno at the helm, but how would they fare without him?

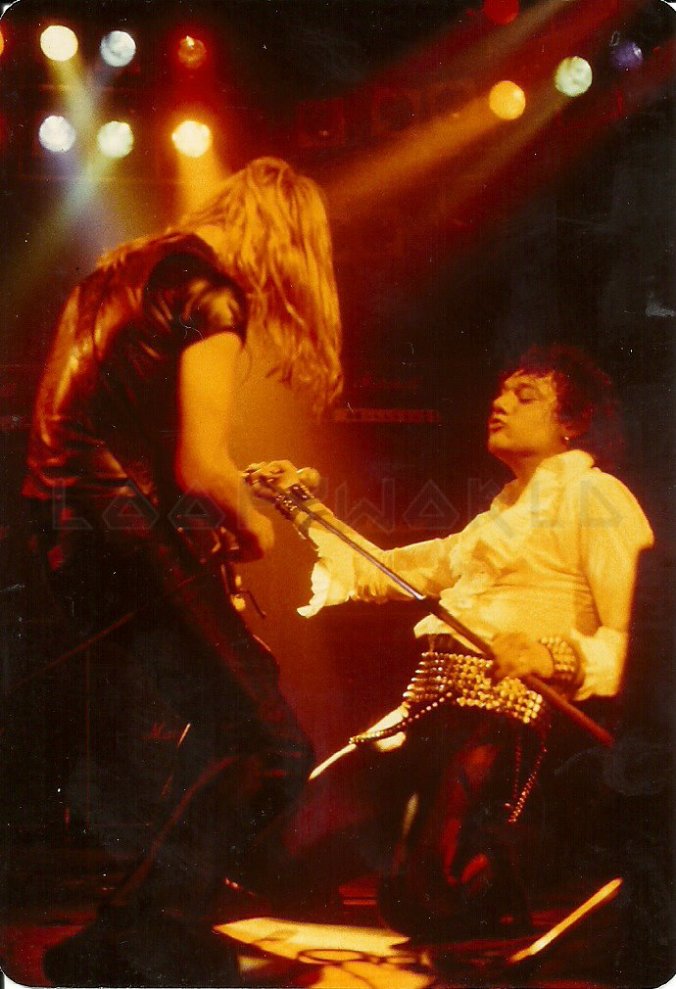

Paul Di’Anno on stage with Dave Murray during the Killers tour in 1981, probably affected by whatever he had ingested the night before or during the day of the gig. (Photo published by Loopyworld.)

This was possibly the first instance of Harris being very nervous, maybe even gloomy, about a change of band members. He later recalled that he thought Maiden’s rise might have ended then and there, fans and critics potentially being unwilling to accept the band with a different voice and a different face.

“I didn’t like to do what I had to do. We were all gutted to lose Paul, and we tried hard to keep him in the band, but he didn’t try hard enough himself. All our lives we’d all dreamt of being in a touring band, but when we got out there Paul wasn’t interested.”

Steve Harris

Harris likely felt the pressure of a crisis situation, caught between Di’Anno’s disinterest and the risk of firing an established lead singer. On the other hand, as Harris later told official Maiden biographer Mick Wall about the nightmarish situation, “We wanted to carry on as we were, but we thought, ‘the longer it goes on, the more we’ve got to risk’.”

A key player in Maiden’s American operation in the 1980s offered sage advice. Bruce Ravid of Capitol Records, Maiden’s US record company at the time, listened to Harris’ worries about setting Maiden back by changing singers. Ravid calmly told Harris that Eddie was the face of Iron Maiden in America, not Paul Di’Anno, and that firmness was needed to progress: “If you’re going to make that change, now is the time to do it.”

Maiden would surely have made the inevitable change in any case, but Ravid’s story illustrates how intensely focused Smallwood and the band was on breaking Iron Maiden in the USA. As a later chapter in our study of Maiden history will discuss, there was a plan in place for the band to gradually win over America in the years from 1980 to 1985, and Di’Anno was putting all of this in jeopardy.

Maiden needed someone to trust.

“SUCH AMAZING POTENTIAL”

Losing their voice could have meant losing the fans that had swarmed to the band in the early years of formation and breakthrough. Di’Anno had been a popular frontman in Britain and Harris feared that Maiden would fizzle out after just two albums, but on the other hand he says, “We knew that if we didn’t do something we’d go down hill pretty sharply and that would be the end of it.”

Di’Anno himself has always claimed that he was getting tired of Maiden in 1981 and considered making an exit. American metal guru Brian Slagel remembers interviewing the singer at the end of Maiden’s 1981 US tour, opening for UFO at California’s Long Beach Arena, where Di’Anno told him that he would leave Maiden. Slagel promised to keep it to himself, but it certainly backs up Di’Anno’s later assertion that getting out of Maiden was on his mind.

Iron Maiden in America in the summer of 1981, an unhappy Paul Di’Anno far right.

In hindsight, it seems clear that Di’Anno was not going to be the frontman that could take Maiden to the biggest stages in the world and provide them with the vocal bravado that would see them rival rock legends like Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple in status. Maiden needed something else, some other ingredient, some X factor that could not just maintain their trajectory but take them to the next level.

“I did tell Rod Smallwood there was no way Maiden would ever break America while Paul Di’Anno sang in the band.”

Dennis Stratton

Harris later told biographer Wall that he always kept his eyes and ears open for potential Maiden singers in the early days, just in case. One of them was Terry Slesser, who had recently replaced Brian Johnson in Geordie when the latter joined AC/DC in 1980. Slesser auditioned for Maiden in secret, probably when the band returned from their North American Killers tour in early August 1981.

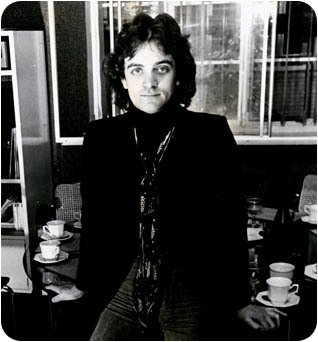

Terry Slesser, probably the only other singer to audition as a replacement for Paul Di’Anno in 1981.

Slesser had previously sung in Paul Kossoff’s Back Street Crawler in the 1970s and also auditioned for AC/DC when Bon Scott died, all of which might give us an inkling that his voice was too deep into the blues to work for Iron Maiden. Indeed, Slesser himself has said that Maiden and him “tried three or four songs, Iron Maiden being one of them,” but that he “couldn’t see it happening.”

If Slesser’s bluesy rasp was a bad fit, Harris has later admitted that Di’Anno’s raspy voice was never the kind he originally imagined singing for Maiden anyway. What did he have in mind, then? A more flamboyant, more operatic approach.

Enter Bruce Dickinson.

His band at the time, Samson, were going nowhere fast. Once Maiden’s rivals on the London scene, they had made poor decisions and had their share of bad luck. Bruce was ripe for another challenge.

Bruce Dickinson, known then as Bruce Bruce, photographed with Samson by Fin Costello.

Dickinson later said that when he first saw Maiden live in 1979 he thought to himself that, “This was just pure Deep Purple … the same shiver up the spine.” Samson were in fact headlining over Maiden that night, but even Samson’s own singer knew that Maiden had blown them away, and he would remember a Purple kind of feeling: “When Maiden launched into Prowler, I got the same goosebumps. This was a modern-day Purple, but with a theatrical side.”

For his part, Harris had always liked Dickinson’s singing, despite not being fond of Samson, and later said, “I thought he sounded a bit like Ian Gillan, actually.” Here was a better fit. Could Bruce Dickinson be the singer that Iron Maiden could trust?

He was practically ambushed at the 1981 Reading Festival when Harris and manager Smallwood flew in from France, with a few hours off from Maiden’s Killers tour, to court the man that Harris in particular hoped could be the new Maiden singer. Dickinson would recall the meeting in his autobiography:

“I was in a corner of a beer tent when Rod Smallwood approached me, saying, ‘Let’s go somewhere quiet where we can talk.’ We walked out and stood, illuminated for all the world to see, under the pole in the middle of the backstage area. ‘Do you want to come back to my room for a chat?’ he said. Back in the room, away from prying eyes, Rod laid out his cards. ‘I’m offering you the chance to audition for Iron Maiden,’ he said. ‘Are you interested?’ I told him what I thought: ‘When I do get the job, and I will, are you prepared for a totally different style and opinions and someone who is not going to roll over? I may be a pain in the arse, but it’s for all the right reasons. If you don’t want that tell me now and I’ll walk away.’ If Iron Maiden wanted to play with the hammer of the gods then bring it on. If not, take a hike and get someone more boring instead.”

Bruce Dickinson

The Maiden manager’s interception of the very young and very self-assured Dickinson meant that this Reading performance would be Bruce’s final appearance as the singer of Samson:

A few days later, sometime in the first week of September 1981, Dickinson led Maiden through songs like Prowler, Remember Tomorrow and Murders In The Rue Morgue in a rehearsal room in Hackney, North-East London. Maiden then headed out for their final four shows with Di’Anno and put Dickinson to a second test as soon as they returned: doing vocals in the studio, performing Twilight Zone among other things. A brief discussion in the studio control room, with Dickinson waiting in the vocal booth, yielded the obvious.

Iron Maiden offered Bruce Dickinson the job.

Bruce Dickinson, not long before Iron Maiden came knocking. He told Harris and Smallwood that if he auditioned he would get the job, and they had to accept him being very different from Di’Anno. Pretty much what they wanted to hear.

All of this was happening behind Di’Anno’s back, but he could scarcely have been surprised to be told that Maiden wanted him to leave. A meeting was called in mid-September, after Maiden’s Scandinavian Killers dates. It had been nearly six months of a tortuous process of disappointment, slight panic, and then finally a decision. The rest of the band didn’t show up as agreed, leaving Smallwood alone to fire Di’Anno.

“It was a civilized discussion. It was literally a case of Rod saying, ‘Paul, we think it’s best if you leave Maiden,’ and me saying, ‘That’s alright, I was going to resign anyway’.”

Paul Di’Anno

More suprisingly, perhaps, the former Bruce Bruce (his embarrassing Samson stage name) seemed uncertain of what to do. He asked several friends and colleagues for advice about the Maiden offer. Whether Dickinson was genuinely unsure is not known. It seems more likely that he could have been nervous about leaving the Samson guys behind for a gig that would obviously pay much better and put him right into a prosperous situation that was already established.

Dickinson’s ex-Shots bandmate Bill Liesegang recalled to the unauthorized Dickinson biographer Joe Shooman that the singer asked him, “I’ve just had this offer from Iron Maiden, do you think I should take it?” Liesegang responded that he thought it was a no-brainer. Dennis Stratton met Dickinson in a pub, probably in the interim when Maiden were off to finish their touring commitments with Di’Anno, where the singer told him about the offer to join Maiden. Stratton recalls: “I said, ‘Yeah, take it. And if you take it, Maiden will be big in America’…”

The outcome was given. Maiden got their man.

One of the earliest photos of Iron Maiden with their new singer, either late 1981 or early 1982. Left to right: Steve Harris, Clive Burr, Bruce Dickinson, Dave Murray, Adrian Smith.

And the band desperately needed not just a capable vocalist, but also someone who could lift the band’s spirit in the wake of a tough tour with uneven performances.

“If I had been looking at the group as a military unit, I would have assessed their morale as being rock bottom. The atmosphere was weary. They needed cheering up. We bonded musically, and I was left to ponder the sad state of affairs that had led to such profound apathy in the face of such amazing potential.”

Bruce Dickinson

The mood in the band would change for the better once Di’Anno was out. It was still a gamble, though, because Dickinson sounded so very different from Di’Anno. After introducing their new singer with five concerts in Italy in late October 1981, Maiden showcased their new line-up at home in London. Officially ending the Killer World Tour at the Rainbow on 15 December and their old haunt Ruskin Arms on 23 December, they would also premiere some new songs:

Both Harris and Dickinson would later admit to being full of nervous energy at this point. But the proof, as they say, is in the pudding. Bruce’s first studio adventure with Maiden produced the classic The Number Of The Beast in early 1982, and they never looked back.

SIX! SIX, SIX!

As Dickinson would later state, a band’s third album can be either the end of the beginning or the beginning of the end. For Maiden it was definitely the album where they promoted themselves into the biggest league. And to do so they had to write a completely new batch of songs, having depleted their vault on the first two albums.

Dave Murray found the band’s new material shockingly fantastic.

Featuring absolutely immortal metal anthems like Steve Harris’ title track and Hallowed Be Thy Name, it is also home to the first Maiden tracks Bruce Dickinson contributed to writing, although uncredited at the time: Children Of The Damned, The Prisoner and Run To The Hills. There is some evidence that he wrote the lyrics for Gangland too, but Bruce himself would rather have that particular fact forgotten, since most of the album was so incredibly good.

“It was all fresh to that line-up, which is one of the reasons it’s such a great album.”

Bruce Dickinson

Adrian Smith found it fresh and exciting too, remembering “going around to Steve’s place – I think he still lived with his gran at the time – and he was playing me the idea for The Number Of The Beast. I thought, ‘Wow. That’s amazing. That’s really different’.” The guitarist would also chip in with song ideas of his own, which he found nerve-racking:

“It’s painful to sit in front of your bandmates and go, ‘This is my idea’, and have them just stare at you. But I thought that if I wanted to stay in the band I’d get pretty frustrated if I didn’t contribute ideas. And fortunately, with The Prisoner, Steve liked what he heard. And 22 Acacia Avenue was something I came up with when I was very young, one of those first songs you write. We were getting stuff ready for The Number Of The Beast, and out of the blue Steve turned to me and said, “What was that song you used to do in Urchin?”, and he started humming it. And it was 22.”

Adrian Smith

The Beast soared to number one in the UK album charts and became a worldwide phenomenon. Iron Maiden had truly arrived. Powered by the relentless rhythms of Steve Harris and drummer Clive Burr, colored by the delicate guitar interplay of Adrian Smith and Dave Murray, the lyrics are delivered with flawless conviction and emotion by Bruce Dickinson, his incredible range and powerful technical ability giving the band many new and exciting avenues to explore.

The Number Of The Beast and the Beast On The Road world tour in 1982 would transform Iron Maiden from struggling nearly-greats to potential world dominators.

As Dickinson later claimed, Harris had found a singer that easily matched him in terms of ambition. “It was Steve’s band,” Dickinson would say. “But I had my own ideas. And I did warn everybody about it before I joined.”

On stage, it was obvious. As Murray later told biographer Mick Wall, “He really knew how to work an audience, and he gave it his all in a way Paul never did.” Indeed, Maiden’s live performance took on a whole other level of energy and appeal when Dickinson arrived:

Many years later, Maiden Revelations would take a look at some of Dickinson’s very best live performances in this feature. We found what was obvious, that Dickinson would become inseparable from the sound of Iron Maiden in a very short time.

“I felt at home straight away.”

Bruce Dickinson

Harris was also energized by the new singer’s arrival, stating a few years later that it was a crucial turning point for Maiden: “When Bruce joined, his enthusiasm was incredible, it was what we needed so bad because the morale of the band was so low.”

It wasn’t plain sailing, though. With Dickinson taking charge of center stage, Harris felt pushed aside. The two would almost literally fight for the spotlight, nearly coming to blows backstage at Newcastle City Hall early in the tour. It had been a long day, first shooting the video for the upcoming The Number Of The Beast single and then doing a two-hour headlining gig in the evening. Smallwood had to physically separate them, with Harris yelling, “He’s got to fucking go!”

Having a new and hyperactive frontman on stage would temporarily make Steve Harris’ blood boil.

But what Harris came to realize was that Dickinson took Maiden to a different league of presentation, showing a hunger for attention and upping of the game which was exactly what Maiden needed. “It might have put my nose out of joint for five minutes,” Harris would later admit, “but then I thought to myself, ‘That’s bloody good, it’s exactly the attitude you want from a frontman’.”

The Iron Maiden live experience had now become something else entirely. Dickinson would not only deliver on the new material, he’d do equally thrilling interpretations of Di’Anno era tracks like Phantom Of The Opera and Wrathchild, and the full two-hour Beast On The Road set in 1982 was a tour de force.

“Studs? Check. Ludicrous trousers? Check. Fist in the air while belting out operatic vocals? Check.” Bruce gives Maiden a new lease of life on their 1982 world tour.

But the difference in the studio was no less significant. Di’Anno’s limited range could quite simply never have accommodated Hallowed Be Thy Name or Run To The Hills. These songs would never have existed.

SINGING A LINE, OR LIVING IT

Longtime producer Martin Birch emphasises Dickinson’s importance to Maiden’s evolution, and explains that the new singer gave chief songwriter Harris the opportunity and means to experiment and be more imaginative. Dickinson could do it all, whatever you threw at him, as the Beast album plainly demonstrates.

Birch and Maiden recorded the new songs in London’s Battery Studios, where they had previously done Killers, in early 1982. The singer remembers the euphoria of listening back to the recordings as Run To The Hills took shape:

“The layered harmony vocals was such a colossal change for the Maiden sound. Our jaws dropped as we heard the rough mixes. There are some songs that you can feel in your bones will be huge.”

Bruce Dickinson

Indeed, Maiden had come a long way since Dennis Stratton got the yellow card for layering harmonies into Phantom Of The Opera on the first album. There was something about Dickinson’s energy and ability that made all of this much more palatable.

Producer Birch says: “Bruce’s was a voice that I could work with much easier. He had a much bigger range, and he could carry melodies where Paul couldn’t at all.” The legendary producer states the obvious, that Di’Anno never could have done it like Dickinson, and that The Number Of The Beast therefore became a historic turning point for Iron Maiden.

Martin Birch knew a thing or two about making classic hard rock records. Here he is with Rainbow: singer Ronnie James Dio (left, later of Black Sabbath and Dio) and guitarist Ritchie Blackmore (right, previously and later of Deep Purple).

But was it easy? No. Dickinson remembers being worn out and utterly frustrated as he tried to deliver what the producer wanted on the intro to the title track. Furniture flew across the studio before Birch called a two-hour break, grinning at the agited singer.

” ‘Ronnie Dio had the same problem on Heaven And Hell,’ said Martin. My head, which ached, and my eyes, which ached, started to pay close attention. ‘He came with the same attitude as you. Let’s bash this one out. And I said to him, no. You have to sum up your entire life in the first line.’ Dimly, I started to see the difference between singing a line and living it. It was like Martin was a can-opener, and I was the can of beans. I thought I’d invented theatre of the mind, but Martin Birch had been doing it for years.”

Bruce Dickinson

Dickinson took the direction, knowing full well the incredible work Birch had gotten out of some of rock’s most legendary voices. As he returned to the microphone he lived the lines of Harris’ mesmerizing opening verse: “I left alone, my mind was blank. I needed time to think, to get the memories from my mind.”

A metal classic was born.

Click here for our review of The Number Of The Beast!

Artist Derek Riggs provides the visual goods to go with Iron Maiden’s breakthrough album The Number Of The Beast, depicting Eddie manipulating the Devil manipulating Eddie.

Iron Maiden would never have become anything close to the monster we know and love without Dickinson. The voice, immediately recognisable. The range, able to handle everything from Sign Of The Cross to Aces High with supreme mastery. The dedication, delivering everything from Charlotte The Harlot to Paschendale with perfect conviction, not to mention theatrics when called for.

If Bruce had sounded more like the clichéd 1980s rock voices of Joe Elliott, David Lee Roth or Mark Slaughter, Maiden would not have lasted the way they have. His voice was built on English 1960s and 70s singers like the aforementioned Ian Gillan, who Harris had likened him to, and the theatrical and operatic Arthur Brown, which gave him a unique identity in the hard rock landscape of the 1980s. Combined with this, his quirky personality made sure things would never be dull, on or off stage.

And how about the songs he wrote or co-wrote? Just tick off how many of these you think of as essential Iron Maiden songs: Revelations, Flight Of Icarus, Die With Your Boots On, 2 Minutes To Midnight, Powerslave, Moonchild, The Evil That Men Do, and so on and on.

Steve Harris found a partner in music that would ultimately prove indispensible when he hired Bruce Dickinson to be Maiden’s singer.

Singer. Songwriter. Frontman. Spokesperson. Bruce was, and is, irreplaceable. But after the success of The Number Of The Beast and the massive 1982 world tour, Dickinson found himself feeling depressed that he had already achieved his dreams: “I was in a great band, I’ve got a number one album, I’ve just done a world tour… What do I do with the rest of my life?”

This restlessness would often come back to haunt him, but at the dawn of Maiden’s classic era he never had the time to ponder it. The Maiden machine rolled on.

THE FINAL PIECE

Needle to vinyl. A slight scratching sound. Then: Tadada-dumdumdum, tadada-dumdumdum, tadada-dumdumdum, tadada-boom! Thus Iron Maiden opened a new chapter in their history, with the new drummer leading the charge. The classic line-up was a reality. The golden age was unfolding, and Maiden were about to explode.

“That’s the fucking line-up.”

Doug Hall, sound engineer

In early 1983, as Iron Maiden faced the momentous task of recording a follow-up to the groundbreaking The Number Of The Beast album, they did so with a new drummer: Nicko McBrain.

Nicko McBrain behind the drums in 1983. He was the final piece of Maiden’s classic line-up puzzle.

McBrain had been playing with The Pat Travers Band and more recently the French band Trust, when the call came from Iron Maiden at the end of 1982. Clive Burr had been asked to leave, and Nicko was asked to come and have a jam with the band. He was then promptly offered the gig, with Harris knowing that “he’d be the right man for the job.” Nicko’s reaction? “I was well fucking pleased!”

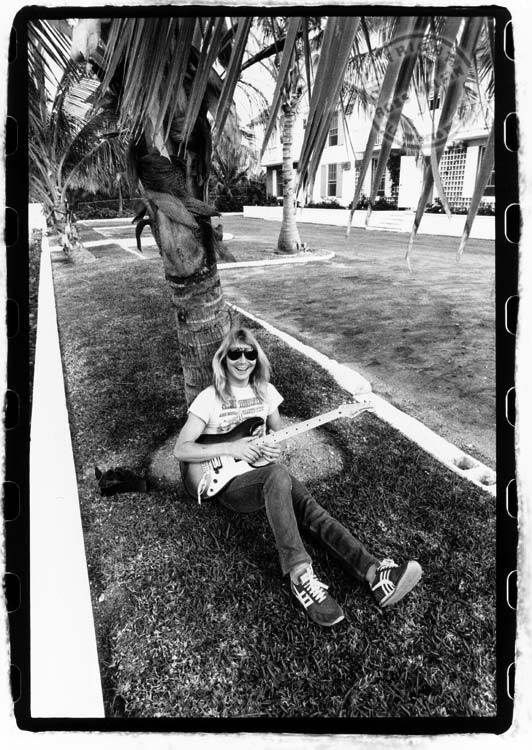

Iron Maiden were soon writing and rehearsing their new songs on the stormy Channel Island of Jersey in January 1983 before heading off to Compass Point Studios in Nassau, the Bahamas to record McBrain’s debut Maiden album, Piece Of Mind.

With Maiden now starting to reap the financial rewards of The Number Of The Beast, Smallwood had decided to bring in his old friend Andy Taylor as the band’s business manager. The management duo quickly advised the Maiden members to invest their first millions in property and to stay out of their home country most of the year to avoid paying UK taxes.

“The options were Air Studios, in Antigua, or Compass Point, in Nassau. Personally, I would have preferred to go somewhere like the Record Plant, in New York, or somewhere in Los Angeles. It would have been easier and we might possibly have got better technical results. It was pretty bare bones down in the Bahamas, but it was sunny, we liked it and it was available, so we decided to do the recording there and then mix it later in New York.”

Martin Birch

Photographer Ross Halfin is on hand to document one of the reasons why recording at Compass Point in the Bahamas was good.

Besides offering a relaxing holiday-like atmosphere, the Bahamas seems to have been an inspiring place for getting the work done too. Featuring timeless masterpieces such as Where Eagles Dare and The Trooper, along with equally impressive rarities like Still Life and To Tame A Land, McBrain’s first Maiden album was an instant classic.

“The best album we’d done up to then, easily.”

Steve Harris

Once again produced by Martin Birch, Piece Of Mind marked the start of a period of stability for Maiden. The Harris-Murray-Smith-Dickinson-McBrain line-up would reach the top of the world during the 1980s, releasing 4 classic studio albums, 1 monumental live album, and traveling the globe on record-breaking world tours.

Iron Maiden had finally assembled the classic line-up.

The eyes of McBrain, in the Flight Of Icarus video.

But the McBrain case is very different from the Dickinson case. The singer replaced someone with an obviously inferior ability. The drummer replaced someone who still commands an enormous amount of respect from fans and critics, Clive Burr. His drumming on the first three Maiden albums was essential in creating the Maiden sound, and his powerful playing was the backbone of their live shows for three fundamentally important years.

So what did McBrain bring to the band that they couldn’t do without?

THE THREE SIDES OF THE CLIVE BURR STORY

The answer might lie in the reasons behind Burr’s departure. As the 1982 world tour dragged on, the drummer became less reliable, as recounted in this feature. In short, Harris claims that he was feeling increasingly frustrated by Burr’s lack of consistency, which the bassist attributed to too much partying.

Murray and Smith have both supported Harris’ assessment, effectively stating that sex and drugs took down Burr as they had taken down Di’Anno before him. The 1982 American tour for The Number Of The Beast was seemingly a hedonistic excursion for everyone except Harris, the band being in the comparatively easy position of warming up for others. As Murray told biographer Mick Wall many years later:

“You’d come off stage before nine, or something like that, and then you’d got all the night to do whatever you want. Everyone was doing their own thing on that tour, and it started getting a bit out of hand, actually. I mean, especially in the case of Clive, or whatever.”

Dave Murray

Clive Burr on stage with Iron Maiden.

Smith would admit in retrospect that there was a certain amount of hypocrisy in pushing Burr away on account of too much partying, and he recently recounted his own excessive experiences of Maiden’s Killers and Beast tours in his memoir:

“Drugs, mainly cocaine, were freely available – no need to buy it as other musos, crew and fans were always offering it around. Booze was on the dressing-room rider and in those days we would always have vodka and brandy along with cases of beer. A little ‘thirsty’ when you’re in your hotel room? No problem: minibar. Tour bus? Always well-stocked.”

Adrian Smith

The difference might truly lie in how well the individual band members handled their responsibilities on stage despite all this, as the intake of chemicals did not necessarily subside just because Di’Anno and Burr were out of the band.

Dickinson, the newest member of the band at the time, has a different perspective when looking back. He claims in his autobiography that friction between Harris and Burr started to simmer during the Beast tour until it reached a point where Harris was dead-set on having Burr out of the band, not necessarily because of booze and drugs.

“It wasn’t about partying, or girls, because everybody was guilty of that at some time or another. ‘Artistic differences’ would be to overstate his creative input. The breakdown of the relationship between a drummer and a bass player is pretty fundamental, especially if the bass player also happens to be the principal songwriter and band leader.”

Bruce Dickinson

The bass player, principal songwriter and band leader has stated that he came close to calling a halt to the 1982 US tour because the band was not functioning as well as they should be on stage. Burr was quite simply fucking up their gigs, in Harris’ opinion. Smith agrees with this, and the guitarist also claims that Burr was given numerous warnings, after which he’d pull himself together for a few shows and then fall apart again. Dickinson also seems to agree with the underlying problem:

“Clive always regarded the Maiden set-up with a jaundiced eye, even as he was held in high regard by fans. […] Where we didn’t see eye to eye was in the intricate and often eccentric fills and time signatures dreamt up by Steve. Their personalities were increasingly on a collision course. Steve was shy off stage, but aggressive and precise on stage. Clive was Mr Outgoing off stage, but often Mr Approximate when it came to precision on stage. […] By the end, Steve took me to one side and said, ‘He’s got to go. I can’t fucking take it any longer’.”

Bruce Dickinson

Maiden roadie Steve “Loopy” Newhouse, who worked for the band from 1978 to 1984, was Burr’s drum tech at this time, and had suffered a strained relationship with what he increasingly considered an arrogant and complaint-prone rock star. Newhouse states that the drummer started relying on him not just to tech but to provide nods from behind the backline to signal time changes coming up. Impossible to verify, it does at least back up the band’s claim that Burr was not quite on the ball.

These two sides of the story, performance inconsistencies meets clashing personalities, do fit each other and make combined sense. But is there a darker third truth here, somewhere beneath the official explanation and Dickinson’s semi-opening of the curtains?

Clive Burr, second from left, towards the end of the 1982 world tour that would be his last with Iron Maiden.

In the mid-1990s, as Iron Maiden’s official biography was being written by journalist Mick Wall, Clive Burr was going through the challenging first stages of a new life after being diagnosed with an aggressive form of multiple sclerosis. Consequently he never responded to interview requests and did not tell his side of the story in the resulting book Run To The Hills: The Authorised Biography Of Iron Maiden.

In 2010, the illness-stricken ex-drummer shared his side of the story in a controversial interview with Classic Rock Magazine. Burr flatly denied the stories of “drugs or too much drink. It wasn’t anything like that.” He said that during the 1982 US leg of the tour he got the call that his father had died and that he had to return to London. He had to leave the tour for two weeks.

What did Maiden do?

According to Clive they called Nicko McBrain to fill in.

And Burr was fine with this. He knew McBrain, who had been around the band quite a bit when Trust supported Maiden on tour. “He loved the band,” said Burr. “He loved being part of it all. And the rest of the band liked him.” When Burr returned to the tour a couple of weeks later, “I could tell something wasn’t right.”

At the end of the tour in December 1982 Burr was told to leave the band. “I was too upset to feel angry about it,” he later said. “I think if you’re going to sack someone, sacking them just after they’ve lost their father is not the best time to do it…” Burr was out, running off to Germany for a while to get away from it all with his mum, and Maiden carried on without missing a beat.

The classic line-up of Iron Maiden in early 1983: Bruce Dickinson, Nicko McBrain, Steve Harris, Adrian Smith, Dave Murray.

So how could Harris have known that McBrain would be the right man for the job? He had undoubtedly had many opportunities to watch McBrain in Trust. But according to Burr, also because McBrain had already done the job for two weeks on tour. And as Smith later stated about Maiden switching to McBrain: “Steve loves playing with him.”

A major problem with Burr’s side of the story is that it seems that his father Ronald died on 25 December in 1982, after the end of the Beast tour. Still, if Burr was merely confused about the order of events but right about sitting out shows, McBrain had a very unofficial, but very public, Iron Maiden audition at some point on the 1982 The Number Of The Beast tour. It’s well known that Nicko filled in for a sick Clive on Belgian TV in April 1982, a playback job, but concert performances on tour are very hard to believe. Would there not be a Maiden fan out there somewhere who remembers seeing Iron Maiden with Nicko in 1982…?

The most likely conclusion is that Maiden in general, and Steve Harris in particular, were upset with Clive Burr’s partying off stage and a growing schism with bass and rhythm guitars on stage. For Harris there must have been a deep sense of frustration at struggling through yet another US tour with Maiden not functioning properly, and he probably also preferred the playing style of Nicko McBrain. As problems mounted during the 1982 American tour, McBrain was kept close in case things came to a head. In recent years, Nicko himself has confirmed this:

“Clive wasn’t doing so well and they asked if I’d consider joining the band. […] Clive shaped up and got himself back into the band, so I was told that I wasn’t required, and they paid me a month’s severance. A couple of weeks later I got another call because Clive had taken a nosedive again, and I was put back on a retainer. […] That same situation happened three times. It was the third time when things didn’t work out for Clive.”

Nicko McBrain

The arguments for making a change grew stronger and stronger during the 1982 tour, much like the Di’Anno situation of 1981, and Dickinson would later state that “we’d obviously been in contact with Nicko to see if he was contracted to anyone else but, until the decision was made over Clive, nothing happened.”

With their recent success in making a tough decision on the Di’Anno issue, Steve Harris and Rod Smallwood stuck to their ideal of progress over caution, and Burr certainly felt hard done by at a time that was already personally trying for him.

Clive Burr passed away in 2013, and he remained proud of his time with Maiden to the last, sometimes relieving his pain and depression by watching old concerts with himself in the band on DVD.

“And I’m right back there. I’m smiling all the way through it. We were a good band, you know.”

Clive Burr

TROOPERS

What Dickinson today calls “self-fulfilling irretrievable disagreements” led to Burr being destructive on stage, according to the singer, slowing down if being told to speed up. Harris simply did not get along with his drummer anymore, and wanted to make sure that trust was the basis of his relationship with Burr’s successor behind the kit.

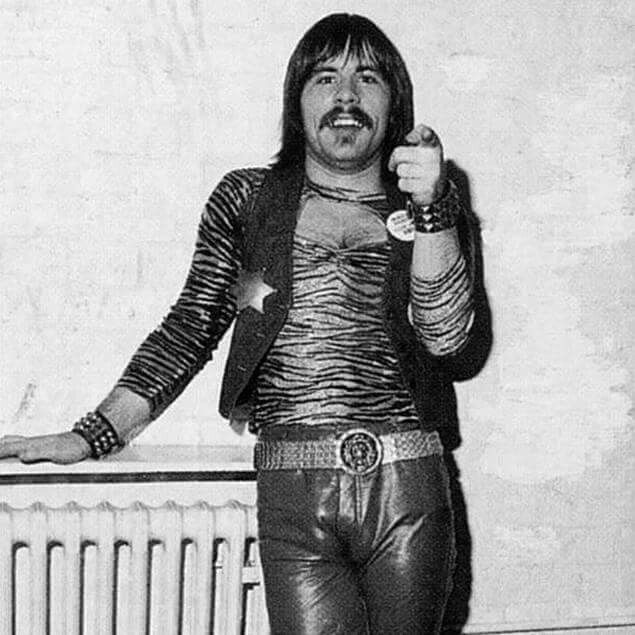

At the all-important dawn of the classic era, inconsistency would not be suffered, no matter what the root cause of the problem was. Iron Maiden needed a drummer who would be completely tour-proof. The unlikeliness of Burr’s partying being the full cause of the problem is borne out by the fact that Maiden hired the ultimate party animal to replace him: Nicko McBrain.

Nicko “sips a drink” in the 1980s.

Manager Smallwood first met McBrain at a party in New York, and says the first thing he thought was “lovely guy, completely mad.” The only thing to change since then is a slight addition to Smallwood’s estimation: “Brilliant drummer, lovely guy, completely fucking mad.” The mad and brilliant drummer himself adds that he and Smallwood “actually met one another in a cupboard. It was one of those sorts of parties…”

The difference between him and Burr, according to Harris’ and Smith’s version of the story, was the fact that McBrain would never let anything get in the way of his performance. Harris once talked about Nicko’s “reserve bag of energy”, trying to put into words how nothing that shakes Nicko up, or brings him down, can ever make a negative impact on a Maiden concert.

Live on stage, Iron Maiden would simply never fail through any fault of their engine Nicko McBrain. The pace and persistence he brought to the band would enable them to face any challenge thrown their way. Or let’s just take it from longtime sound engineer Doug Hall, who beams at the thought of this line-up’s arrival: “Now they’re there, that’s the fucking line-up. I tell you, whoa. You wouldn’t want to follow this group on stage.”

Iron Maiden live on the World Piece Tour in 1983, a group you would not want to follow on stage, according to front-of-house sound engineer Doug Hall.

Whatever happens, Nicko delivers. Something Harris does not fail to appreciate. The bassist says that no matter what McBrain has been up to, “it’s never affected his gig.” The rest of the band can concentrate on their own tasks, and they never have to worry if their drummer is going to be alright on the night.

“I know he’ll be right on it the minute we step onstage,

and that’s priceless to me.”

Steve Harris

Maiden’s performance consistency increased with the addition of McBrain, highlighted by the band’s first headlining tour of the US in 1983.

In fact, this strength seems to have been forged before McBrain even played a gig with them, in the rehearsal rooms and studios where Piece Of Mind was created. Both Dickinson and Smith have been clear that Nicko’s style influenced their writing and deepened their musicality.

“We entered a whole new world with a leap of faith and a new drummer.”

Bruce Dickinson

It may be easy to forget this, but the way Maiden not only followed up Beast in 1983, but actually transcended it, is nothing short of mind-blowing. And it’s equally impressive how McBrain took up the mantle and sounded like he had never done anything but play drums in Iron Maiden. Many years later, Harris would look back and praise McBrain enthusiastically:

“Nick plays drums the way most guitarists play their guitars – he’s riffing along with you, note for note. He doesn’t just hold the beat, he drives the whole thing along. The bass player has to work to keep up – that’s great for me. None of us are allowed to give less than 100 %.”

Steve Harris

McBrain finds his place at the table, and never leaves. Photographer Simon Fowler shot the inner sleeve photo for Piece Of Mind, an album that had the working title Food For Thought.

Guest writer Adam Hansen highlights old flat-nose’s importance to Iron Maiden by discussing some of McBrain’s best live performances in this feature. As Adam points out, it’s not just faultless reliability that is Nicko’s strong point: It might be easy to overlook the fact that McBrain’s drumming style is more playful and less regimented than Burr’s.

The result of this is possibly a less intense but more sophisticated Maiden sound. There is no professionally shot complete concert available from the World Piece Tour in 1983, but bootlegs give a fair impression of the powerhouse that Iron Maiden had become, like this video from Montreal, Canada:

Harris and McBrain holds the groove down in a manner which is usually not as frantic as the 1980-82 aesthetic (although McBrain could certainly go OTT in his pace sometimes), but just as precise. The obvious upside to this is the creation of sonic breathing room for the guitars and vocals to shine. Without this dynamic, Maiden would have been a different band.

“Nicko always had the chops and the technique, but in Maiden he really exploded, to the point where a lot of the stuff we did after he joined was then founded on his playing, all those busy patterns he does, displaying tremendous technique.”

Adrian Smith

Iron Maiden might not have been as strong and long-lasting as they turned out to be, without the inimitable McBrain driving them forward. His 1983 album debut certainly ranks among the most assured and effortless ever for someone coming into an already established band.

Click here for our review of Piece Of Mind!

Eddie brings world piece in celebration of Maiden’s first headlining world tour.

As the World Piece Tour came to a close in late 1983, Iron Maiden were on the brink of becoming the world’s biggest metal band. That throne would finally be theirs after the major efforts of 1984 and 1985:

Height of the Classic Era, 1984-85.

But 1983 was a key year in the history of Iron Maiden. It saw them stabilize at the highest level by releasing the masterpiece album Piece Of Mind, successfully headlining everywhere including the USA, and settling on a top-notch line-up.

All was set for the final step of the masterplan.

Sources: Uncredited 1987 interview logged at MaidenFans.com, Iron Maiden: Infinite Dreams (Dave Bowler & Bryan Dray, 1996), Run To The Hills: The Authorised Biography of Iron Maiden (Mick Wall, [1998] 2001), The History of Iron Maiden, Part 1: The Early Days (DVD, 2004), Metal Hammer presents “Iron Maiden: 30 Years of Metal Mayhem” (2005), Classic Rock‘s “Iron Maiden: Hope And Glory” (Paul Elliott, 25 May 2011), Rhythm presents “100 Drum Heroes” (Edited by Chris Burke, 2015), Classic Rock‘s “How Iron Maiden Made The Number Of The Beast“ (Paul Brannigan, 11 October 2016), Loopyworld: The Iron Maiden Years (Steve “Loopy” Newhouse, 2016), Bruce Dickinson: Maiden Voyage (Joe Shooman, [2007] 2016), What Does This Button Do? (Bruce Dickinson, 2017), Iron Maiden Album By Album (Martin Popoff, 2018), Classic Rock Platinum Series and Metal Hammer present “Iron Maiden” (Edited by Dave Everley, 2019), Monsters of River & Rock: My Life as Iron Maiden’s Compulsive Angler (Adrian Smith, 2020).

Great and comprehensive article – thanks

Pingback: FROM THE VAULT: Live in New York 1983 | maidenrevelations

Bruce didn’t write any music for TNOTB, he said that he made some moral contributions for the songs you mentioned, which is something else. If you are a musician you know what that means. It has more to do with the feeling of the song, for example changing the tempo, singing the melody an octave lower or ad harmony to a melody. If Dickinson had, say written the verses for Children of the damned he would have said that. But he didn’t. Everyone ads their flavor to songs in a band, certainly in a band like Maiden, even if only one person came up with the main parts. Harris has added his bass lines, his flavor to songs like Flight of Icarus and Powerslave. If you have came up with a main part of Maiden song you surely get credit, but there are exceptions; Gers didn’t get credit for Bring your daughter, but that had to do with some contracual issues …

GREAT SITE BTW!

The point is that Bruce hasn’t claimed to have written something like verses for Children because he couldn’t say that anyway, for some reason or other. Contractual issues, sure, and I’m speculating that there was something in those contracts about credits. Steve talks about it in 1990 when Janick comes in, that no one gets more than a wage on their first run, and then they’ll see about royalties if things work out. Bruce claims to have written stuff like the drum part at the start of Prisoner, and I think this is where his “moral contributions” becomes a euphemism for him doing more songwriting than he was credited for, not just regular band work. There’s more about it here: https://maidenrevelations.com/2017/08/15/feature-friday-into-darkness-1992-1993/