The 1990s had arrived and Iron Maiden were about to face many years of tough challenges. This chapter in our study of Maiden History discusses the first line-up change since 1983 and the making of No Prayer For The Dying.

It’s been over 30 years since Adrian Smith left Iron Maiden and Janick Gers joined in his place. Over 30 years since Maiden entered the 1990s with a line-up change, a new album, and a new sound.

Why did Maiden take a musical left turn after the success of Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son in 1988? Why did their first 1990s album sound so different when everyone in the band was proud of the final album of the 1980s? Why did Adrian Smith leave the band? How did Janick Gers come to join in his place?

These and other questions will be discussed in this chapter as parts of 5 MAJOR CHANGES that swept Maiden in 1990.

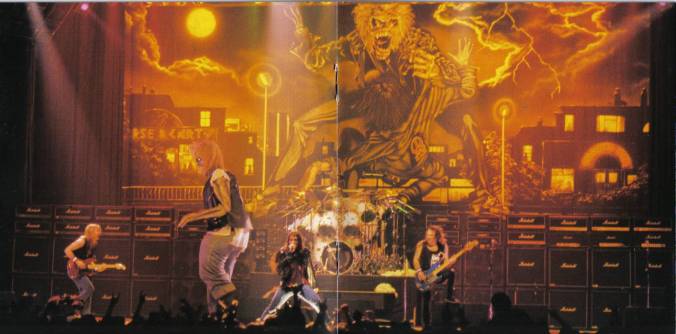

A triumphant Iron Maiden on stage in 1988, touring for their Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son album and seemingly very happy about it.

…AND WILL I TRANSCEND?

In late 1989 Iron Maiden gathered at the release party for the Maiden England concert video. Celebrating the end of Maiden’s incredibly successful 1980s period, the video featured the band live on stage at the climax of the Seventh Tour Of A Seventh Tour, powering through a set of already classic material from their first seven studio albums.

The full tale of Maiden’s triumphant finale to the 1980s, a period of immense productivity and both artistic and commercial success, is told in our previous chapter on Maiden’s history:

End of the Classic Era part 2, 1988-89.

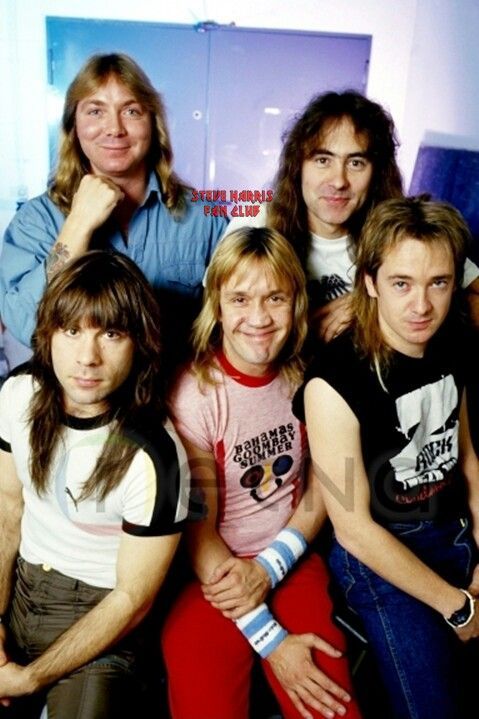

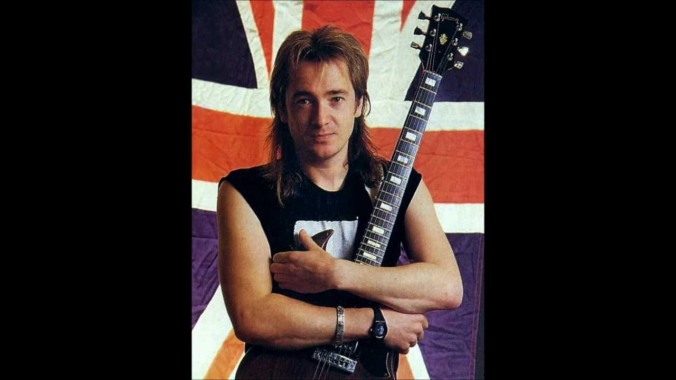

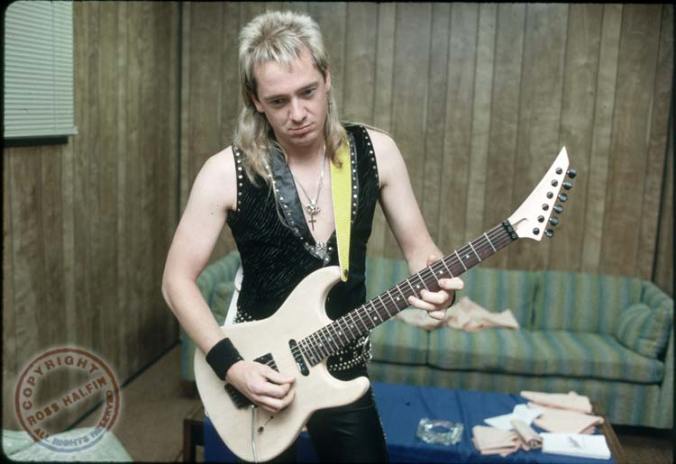

Iron Maiden’s classic line-up pictured in 1988: Adrian Smith, Dave Murray, Bruce Dickinson, Nicko McBrain and Steve Harris.

If anyone at the release party had a sense that Iron Maiden were about to enter a period of changes, they probably didn’t have a clue quite how massive those changes were going to be. Within four years two of the most prolific songwriters in Maiden would be gone, and even the voice of the band would be changed.

Maiden had arranged to meet up in January 1990 to start work on their first album of the new decade, but they would face their first 1990s challenge almost as soon as the first chord was struck. A big question for their new project was whether to go beyond their late 1980s sound and further pursue the direction of Somewhere In Time (1986) and Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son (1988), or to go back to something less ambitious and more akin to an earlier time in their history.

GOING SOLO, part 1

At the time of the Maiden England release in November 1989 Iron Maiden had enjoyed their first ever year off from band activity. Bassist and band chief Steve Harris had spent the first half of the year editing the new concert video, while two other members of the band had immersed themselves in adventures that were to impact Maiden’s development in ways that no one involved had originally intended.

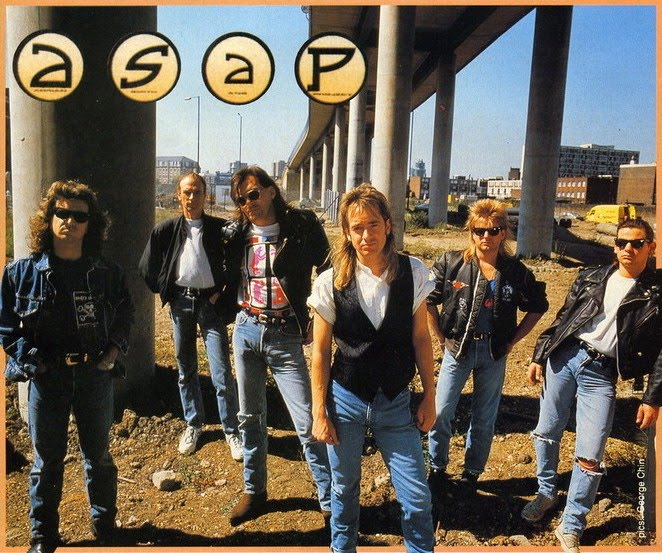

Guitarist Adrian Smith had spent his time off from Maiden forming the band ASAP (an acronym for Adrian Smith And Project). He had wanted to do something outside of Maiden for a while, and ASAP was built on the one-off side project Smith and drummer Nicko McBrain had put together in late 1985, named The Entire Population Of Hackney, designed to stave off boredom in the hiatus following the massive 1984-85 World Slavery Tour.

“Nick said, ‘I’m bored, do you want to play?’ So we’d get together in a London studio. We did a couple of gigs, and then a few years later, I’d written a few songs, and the Maiden guys encouraged me to do an album. They said, ‘Why don’t you do an album?’, and EMI were into it.”

Adrian Smith

The 1989 ASAP music that resulted from all this was definitely not derivative of Smith’s writing in Iron Maiden, but no one should have been too suprised to hear the guitarist take a different direction.

ASAP, the first Adrian Smith solo project, was a very serious and sombre affair, designed to impress America.

Adrian had thoroughly enjoyed the experimentation of the previous two Maiden records, Somewhere In Time and Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son, and the fact that Maiden picked up on stuff like Wasted Years and the eventual single B-sides Juanita, That Girl and Reach Out encouraged him to take his explorations further. As Smith explained to Maiden biographer Mick Wall:

”That’s when I started making demos of material that Maiden wouldn’t have been interested in. Up till then, I would tend to discard ideas unless they were obviously gonna work for Maiden.”

Adrian Smith

A risky inclination, perhaps, as fan favorite Wasted Years would have stayed in the pile of unfinished not-for-Maiden ideas unless Harris had heard it by accident on Smith’s idea tape. In any case, Smith’s new diligence in working up non-Maiden tracks resulted in a batch of completed songs, the formation of the ASAP band, and the recording of Silver And Gold (1989) in London with producer Stephen Stewart-Short.

The end of which decade? Hair speaks a thousand words, as ASAP pose for their album release in 1989.

Maiden manager Rod Smallwood was enthusiastic about the material and the notion of Smith doing a solo album that would cater to his more ”commercial leanings”, as Rod said, and maybe even provide a hit in America that would reflect well on Maiden. The manager had successfully implemented a five-year plan for Maiden to break the US in 1980 to 1985, but had to see his second five-year plan for 1985 to 1990 hit a snag when Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son “didn’t move on a step in America”, as he put it.

A high profile Adrian Smith record might arrest Maiden’s falling star overseas, the manager thought. But when Silver And Gold was released in September 1989 it immediately tanked and quickly disappeared from view.

”It wasn’t metal enough for metal fans, and the fact that I was in Maiden didn’t cut any ice with the potential new market. It was a non-starter, commercially.”

Adrian Smith

One would think that Smith was made aware that the best place for him to be was in Iron Maiden, but the process of getting on with Maiden business would be more complicated than merely wanting to be there, as we shall see.

GOING SOLO, part 2

At the same time as Smith’s exploits, singer Bruce Dickinson also happened to make his first solo album, as the result of a series of coincidences. In early 1989, Harris had been asked by Maiden’s publishing company Zomba if the band could contribute a new track to the fifth instalment of the A Nightmare On Elm Street movie franchise, but he was busy with the Maiden England video. When Harris passed, the request was put to Dickinson instead. Smallwood asked the singer if he had “anything kicking about”, Dickinson would remember, “and I was like, ‘Yeah, definitely!’ You know, lying.”

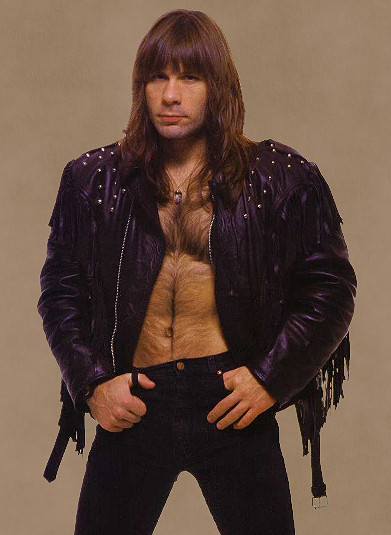

Not quite Axl Rose, but Bruce Dickinson entered the 1990s with style. Now he needed to write and record a song for the Elm Street soundtrack in a hurry.

Bruce had to scramble. He cooked up a song and decided to call a mate that he was currently seeing quite frequently down the pub: Janick Gers, a guitar player formerly of White Spirit and Gillan who was down on his luck.

“As we sat having a beer, he seemed resigned, somewhat depressed about the state of the music industry, saying, ‘They’re more interested in your fucking haircut than whether you can play guitar.’ Janick was selling his equipment: his old Stratocasters, cabs and vintage Marshall amps. He was doing a sociology degree and thought about teaching.”

Bruce Dickinson

Would Janick want to do the Nighmare track with Bruce for a bit of fun and a bit of cash? After all, Dickinson thought, “he was far too good to be wasted on teaching sociology.”

“I went ’round to see him and he brought out this song that sounded AC/DC-ish, and I said, ‘Nah, it wants to be more like…’ So I put the chords in and then we re-did the chorus. He was trying to get away from the Maiden sound, so he was very open to ideas.”

Janick Gers

Around this time Dickinson would hear Gers’ collaboration with former Marillion singer Fish, the track View From The Hill on Fish’s first solo record Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors. The Maiden frontman thought to himself that “Fish is mad to loose this guy. He can really write as well as play.” What Fish threw away, Bruce could pick up and play with.

After delivering his Janick-fueled debut solo song, Bring Your Daughter…To The Slaughter, the singer was happy to learn that Zomba loved the track and wondered if there was any more like it. ” ‘Oh yes, loads,’ I lied,” Dickinson would remember.

Voilà, an album project! Dickinson threw Gers another lifeline and the two of them went about writing an entire album in one mad rush, working in Gers’ front room in London’s Hounslow suburb. They quickly assembled a band and recorded the songs with producer Chris Tsangarides and engineer Nigel Green in Battery Studios in the summer of 1989.

The resulting album was the pastiche-fest Tattooed Millionaire, released in the spring of 1990. Dickinson is clear in retrospect that it was never intended as anything more serious than a good time with mates, and absolutely not as a statement of artistic ambition beyond Maiden.

”Tattooed Millionaire didn’t really fullfill any passionate longing. It was just a rock’n’roll album … I think if anybody was going through a phase of trying to do something deeper, it was Adrian, not me.”

Bruce Dickinson

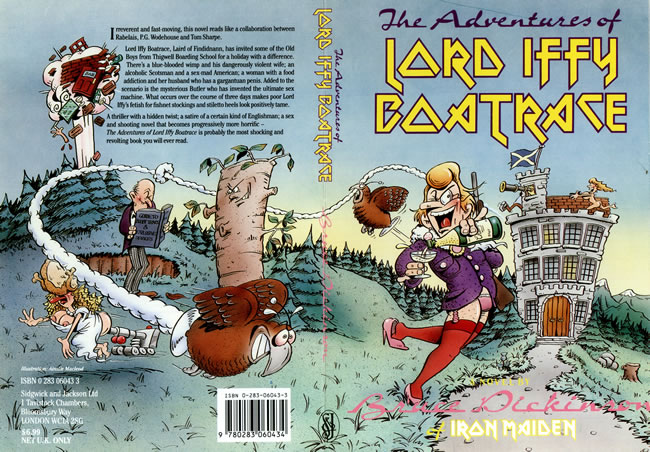

Dickinson had not intended to fill his year off from Maiden with any kind of musical activity, prefering to focus on fencing and other interests. These other interests had come to include authoring novels, a pastime he’d taken to a few years earlier on the Somewhere In Time tour. As Steve Harris said at the time, “We’ll be on a plane and while I’m reading a book, he’s bloody writing one!”

This eventually resulted in the publishing of The Adventures Of Lord Iffy Boatrace in 1990. As with his solo album, it was never designed as an alternative to continuing with Maiden, merely as a way of staying busy while the mothership was docked.

Bruce Dickinson’s satirical debut novel, featuring Lord Iffy, an upper class semi-transvestite land owner.

Even so, many observers thought the singer might jump ship at the time of Tattooed Millionaire, and Harris was one of them: ”I actually said to Rod, ‘I hope he doesn’t fuck off and leave us in the shit, ’cause at this stage to find another singer would be very bad news!’”

That sentiment would come back to haunt the bassist a few years later, but at the time Dickinson assured Harris that he was still 100 per cent into Maiden, and he insists to this day that he was very happy to return to his day job for their first 1990s adventure.

But stormy seas lay ahead…

NO PRAYER FOR ADRIAN

Iron Maiden set up shop at Harris’ mansion near Harlow, Essex in January 1990 to write their first album of the new decade. The plan was to take more time writing than they had done in the past – through January, February and March – and then record the new album at London’s Battery Studios in April and May.

For Smith this was a very positive thing, as he felt strongly that more time for writing would be important to the band’s development. But Maiden’s songwriting had always been swift, and with the longest ever gap between albums to that point most of the band was extra geared up to get going.

Harris and Dickinson both had a bunch of ideas to bounce off each other, and the pair sat down to work. Harris boasted of their pace: ”When we got together for a writing session one day we ended up putting together Tailgunner, Run Silent Run Deep and Holy Smoke all in one day!”

Harris and Dickinson got into frantic creative activity when they started work on Iron Maiden’s first studio album of the 1990s.

Smith on the other hand was slow in getting going, only coming up with Hooks In You in the first couple of weeks. He wanted and needed more time to build new ideas and construct songs, something the original plan would facilitate: ”The plan was to spend three months writing together at Steve’s,” Smith recalled years later, ”taking our time and getting a vibe going.”

But the burst of creative energy between the singer and the bassist yielded CHANGE #1 – a stylistic shift, an intention to go back to basics, back to a street-level sound, making a kind of anti-Seventh Son album.

Smith was taken aback by this unforeseen left turn.

”The vibe was, ’Let’s go back and make a really raw-sounding album like Killers,’ and I didn’t want to do that. I thought we were heading in the right direction with the last two albums. I thought we needed to keep going forward.”

Adrian Smith

With a handful of songs done in record time, Harris and Dickinson agreed to ditch the original plan of writing for three months in Essex and then recording in London in the spring. The new idea was to call in producer Martin Birch at once and get a mobile recording unit to tape the band in their rehearsal room. Smith felt devastated by the change of plans, later stating that he was ”completely thrown by the idea.”

Steve Harris’ mansion in Sheering near Harlow, Essex. The brown barn to the left was converted into a rehearsal room and later a recording studio. Maiden’s first project there was the writing sessions for Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son, and in early 1990 they would write and record No Prayer For The Dying there.

With Harris and Dickinson in agreement about the direction of the music and the method of recording, there was very little Smith could do to alter the course of proceedings. The singer was fired up by a quick and energetic approach that resembled the way he had recently created his first solo album.

”I was as responsible as everyone else in saying: ‘Oh yes, let’s go and do it in a barn with a fucking antiquated recording mobile.’ ”

Bruce Dickinson

At the time, Harris’ enthusiasm was obvious: “Originally we were going to do it at Battery Studios in London in April, but we were ready early. And we were so fired up we thought, fuck it, let’s do it now, let’s get a mobile in.”

Despite Smith’s misgivings, Birch and the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio were called in. According to Harris, the band had only rehearsed four songs at that point – Hooks In You, Holy Smoke, Public Enema Number One, and The Assassin. Smith would later look back on the rushed situation with a palpable sense of fatigue and frustration:

“We didn’t have that many songs. To be honest I was really struggling in the writing. I desperately wanted to write something brilliant, you know, as everybody does. But I just… I was struggling. I was struggling, struggling, struggling. I don’t know why. ‘Cause I was trying too hard, probably. And we started recording. I don’t know… We actually started working, and I think my lack of enthusiasm just got on the other guys’ nerves, and so, that was it really.”

Adrian Smith

Recording got underway, whether Smith wanted it to or not, and Harris and McBrain put down the basic tracks for The Assassin. But within a matter of days a bombshell shook the band. CHANGE #1 led directly to CHANGE #2, the departure of Adrian Smith from Iron Maiden.

The classic line-up of Iron Maiden came to an end in January 1990.

The build-up to this point can be traced way back to Maiden’s perpetual grind of albums and tours throughout the 1980s. Smith recently opened up about his experience of this period in his own memoir. The wild partying of the early 1980s had been at least partially to blame for Paul Di’Anno and Clive Burr losing their jobs, and Smith admits to struggling with life on the road even as Maiden seemingly settled down to being a dependable headlining act.

“The second half of the 1980s saw more of a responsible attitude on my part. That’s not to say I lived link a monk, and ten months on the road were still littered with plenty of heavy nights. I also suffered with depression from time to time, and drink and drugs only served to aggravate the symptoms. I was quite shy by nature so drinking became an obvious crutch. Sometimes I wish someone had put an arm around my shoulder and got me some help. Instead, eveyone just used to laugh at my pissed-up, coked-out antics. So, in a nutshell, that was my eighties. A decade of incredible highs and some barrel-scraping lows.”

Adrian Smith

There was certainly a dark side of Maiden’s relentless drive to conquer the world, and added to the inevitable burn-out resulting from the above, Adrian Smith was even quite unhappy with the exaggerated tempos and overloud sound of the band’s live performances in their most successful era. He clung to the wish and hope that their sophisticated late 1980s material could be given more room to breathe on stage, but now his love for that material was also being negated by the band’s new direction.

”Adrian seemed really negative about a lot of things. He just didn’t seem to have the passion anymore.”

Steve Harris

Adrian Smith was put off when Maiden decided to write a simpler back-to-basics album, ditching their late 80s aesthetic, and to record it as soon as possible on a mobile studio.

When Smith questioned the band’s current notions, he was challenged to explain himself. As the guitarist later recalled: ”I said, ‘Well…’, and took a deep breath and went on for about an hour, talking about how I felt.”

Smith insisted he was still happy to contribute to Maiden, despite having enjoyed his solo project, but he was unhappy that the new recording plan left him little chance to actually do so.

”It all happened over a couple of agonising days. There were lots of long phone calls. It was all very emotional.”

Adrian Smith

In retrospect Dickinson would see the signs of Maiden’s 1990s problems in what Smith was trying to express, and how the band reacted, writing in his memoirs that, “Conversation turned into accusation and, in the end, it was our own hubris, fuelled by our seemingly untouchable success, that sealed his fate.”

Smith disagreed with the musical direction for the new album, wanting to continue down the road that had been travelled in 1986-88. At any rate he was put off by the change of plans that interrupted the writing process they had agreed to, and he questioned the wisdom of a cheap mobile recording.

He must also have been dreading a year on the road when he was unhappy with both the new direction and with the band’s live performances of the period.

When Eddie was finally unleashed on the world anew in late 1990, here in the Derek Riggs artwork to first single Holy Smoke, Iron Maiden had gone through their first change of guitarists in nearly a decade.

It was a reluctant parting of the ways that was pushed into effect by Harris, who probably believed that the most important thing was to keep Maiden’s energy going, not allowing the shark to stop moving.

Dickinson later admitted that Smith ”wasn’t fired but he didn’t quit entirely willingly … he sort of agreed to leave.” Smith told Harris that he was 90 per cent into it, and the band chief replied that only 200 per cent would do. Smith yielded.

“He clearly wasn’t happy with the current state of affairs, but I don’t believe he wanted out; he just wanted to make it better.”

Bruce Dickinson

A Ross Halfin shot of Adrian Smith on tour in 1988. The guitarist was happy to go down the road that Maiden chose with Somewhere In Time and Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son, but not as happy with the band’s live performances at the time.

However, a myth did take form in the wake of Smith’s departure: that he wasn’t interested in metal music anymore. Harris did his part in promoting this idea, saying at the time that, “I think maybe that was why Adrian wasn’t into some of the new material, cos it was far more on the heavy side this time around.”

This speculation is somewhat perplexing, as it’s hard to argue that Maiden’s new songs in 1990 were heavier than Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son. But Smith was aware that his ASAP record had “perhaps sent the wrong signals to the band in some way, like they were worried that I wasn’t into doing metal anymore.” Three decades later Smith would still say that, “I think it shocked the guys in Maiden a little, but it shouldn’t have done, because Urchin wasn’t a heavy metal band.”

It certainly became the default explanation at the time, in papers and magazines, that Adrian Smith left Iron Maiden because he wasn’t into heavy metal anymore, but it simply wasn’t true. In any case, it was the end of the road for Smith with Maiden at a critical point in the band’s history. He was out.

Was it right? Was it wrong? It’s easy to see Harris’ point of view about wanting all members of the band to show the necessary fire and dedication. But what about the other point of view? Let’s be honest:

Adrian Smith was expected to be as excited about the new direction and the record-it-at-once-on-a-mobile-in-a-barn method as everyone else, but in essence he had been blindsided. The band didn’t stand by their plan to write for three months to develop their first 1990s album, and once the big discussion came, the mobile and Birch were already there and recording. Adrian’s argument was that they shouldn’t do what they were already doing.

THIRSTY WORK, MAKING HOLY SMOKE

The severely amputated writing schedule threw things up in the air. Even if the band had wanted to get a real studio at that point, they probably couldn’t have done so on such short notice.

In effect, Harris and Dickinson championed a last minute rethink of a carefully planned year of activity, and found themselves without a proper studio for recording and with one guitarist less to do the work.

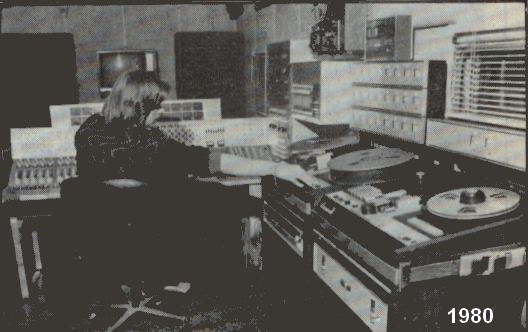

The inside of the Rolling Stones Mobile Studio that was used for the recording of Maiden’s 1990 album, cirka a decade prior.

To solve problem number one, get a mobile studio! Luckily for Maiden, Martin Birch was semi-retired at that point and worked only for them. Which meant he could be called in on short notice. The legendary producer was not enthusiastic about the mobile solution.

”Martin Birch suggested that we do the album in a proper studio, but everybody was like, ‘No, no, no, this’ll be really cool.’ And Martin did the best he could.”

Bruce Dickinson

To solve problem number two, get Janick Gers! Harris thought the Tattooed Millionaire guitarist might be exactly the person Maiden needed: ”Good guitar player … Great onstage … Good bloke.” With no time to lose, Dickinson called Gers and asked him to learn The Trooper, Iron Maiden, The Prisoner and Children Of The Damned. Janick would recall the strange request years later to Maiden biographer Wall:

”I got a phone call one afternoon from Bruce. He said, ‘Would you learn some Maiden numbers?’ The first thing I said was, ‘No,’ because we’d agreed we wouldn’t do any Maiden numbers.”

Janick Gers

Gers was looking forward to a club tour with Dickinson’s solo band in the summer of 1990, for which a strict no-Maiden policy had been agreed upon. But the singer explained that Maiden were in fact hoping to replace Adrian Smith with Janick Gers, and the prospective Maiden guitarist turned white as a sheet. Iron Maiden without Adrian seemed unthinkable at that time, and Maiden with Janick in it was no less alien a concept.

“I’d never worked with another guitar player before. I’d only worked with a keyboard player, so to be honest I didn’t think I’d fit in with Maiden. Anyway, I went along to rehearsals thinking that it wouldn’t be right for me, playing with another guitarist.”

Janick Gers

Gers auditioned the next day, suggesting that they start by blasting through The Trooper. It was a done deal right away, as Gers recalls: ”The whole thing just took off. When we finished, I was shaking with the adrenaline, and I remember Bruce saying, ‘Shit! That sounded incredible!’”

A Ross Halfin shot of Iron Maiden in 1990: Janick Gers, Nicko McBrain, Bruce Dickinson, Dave Murray and Steve Harris.

CHANGE #2 had led to CHANGE #3: Janick Gers was the new guitarist in Iron Maiden. Recording commenced immediately and was completed in about three weeks. Gers worked in a very different way from his predecessor, as Harris explained: ”Recording with Janick is interesting. You have to get him in one or two takes, otherwise it just isn’t happening for him, that’s how he is.”

Which suited the new Maiden ethos just fine. Birch worked his magic as best he could on the mobile unit and later mixed the album at Battery Studios. The first Maiden record of the new decade would be titled No Prayer For The Dying and released on 1 October in the fall of 1990.

BUSINESS OF THE BEAST

The band launched their new campaign by heading out on a UK tour of smaller venues, another one of the back-to-basics efforts of 1990. And indeed, the new-look and new-sound Maiden seemed to fit theaters better than they would arenas.

In what might have been a natural reaction to the big productions of the 1980s they made CHANGE #4: Dropping the pyro and the elaborate sets in favor of Marshall stacks and simple lighting.

”We thought the Seventh Son stage show just got a bit out of hand, and we just wanted to get away from all that and turn everything into a massive club gig again.”

Steve Harris

It was certainly what many music journalists were asking for at the time, that Maiden abandon their 1980s fantasy style and get more realistic. In the early 1990s a Metal Hammer writer confronted Dickinson, stating that Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son was “confused” and that the tour was “pantomime”. Dickinson agreed:

“Yeah, I think you’re right. That was a flawed album and the tour was too much. We forgot about the music.”

Bruce Dickinson

Iron Maiden on stage in 1990, featuring Eddie but staying away from the thematic set designs and special effects that had marked their stage shows in the 1980s.

Dickinson owning up to Seventh Son being confused and flawed, and agreeing that the band forgot about the music on what the journalist calls a pantomime tour, makes for a stark contrast to the singer’s positive opinions and statements about the album and tour both before and after the 1990s. In retrospect this should probably be considered part of an attempt to stay cool in the new decade.

Indeed, Maiden plotted their course for the 90s by making an apparent effort to de-Tap their live show. Although it could very well be asked if walls of Marshalls were any less Spinal Tap-ish than their earlier thematic productions…

Click here for our look at Maiden’s 1990s stage productions!

Maiden’s story, in short, was that they thought their late 80s stage shows were overblown and that they had seen the error of their ways. Quite simply, toning down was the right thing to do, artistically speaking.

However, could there be something else behind all this? Maiden are in the music business, after all. And what would be the business consequences of halving their US record sales and slicing their concert attendance too? This is precisely what happened in 1988, while Maiden were still touring with an excessively expensive production:

In 1988, Maiden’s crew and production must have been as big as ever. But their US success was waning, with album sales down about 1 million units from the previous record. Tour attendance consequently shrank, which would have greatly affected the ever important sales of merchandise.

Co-manager Andy Taylor, Smallwood’s life-long partner in crime and Maiden’s deeply respected business guru, has been remarkably open about the state of Maiden’s affairs as the 1990s dawned: “In the late 80s we had a couple of tough years, but we worked it out and came out the other end.”

Cue a home studio and a bare-bones stage production.

FATES WARNING

But why did Maiden make a considerable musical change from 1988 to 1990? The question is somewhat puzzling in light of how strongly the band felt about Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son. Harris is on record time and again saying it’s one of his absolute favorite Maiden albums, and Smith left the band partially because they abandoned that direction.

Dickinson was outspoken back in 1988, stating that ”with Seventh Son I think we’ve shown the way for heavy metal in the 1990s.” But in 1990 the Seventh Son style was exactly what the band tried to get away from, as they seemed to agree with music journalists that they had gone wrong in 1988.

There is a road and there is no prayer for the person that Eddie grabs hold of on that road. Yes, it’s Derek Riggs’ artwork for No Prayer On The Road, the Maiden tour of 1990-91.

How did it all turn out?

The single Bring Your Daughter…To The Slaughter, somewhat perversely released on Christmas Eve 1990, gave Maiden their first number one hit single in the UK, which Harris took as a sign that Maiden’s change of direction was the right thing to do: ”It just made me feel excited again, like it really was all worthwhile, like a vindication that we must be doing something right.”

Were Iron Maiden really vindicated by having a number one single?

In truth, the single’s chart success depended greatly on the cynical move by EMI and Smallwood to release a whole host of different formats that would all be purchased by loyal fans around the UK. But in any case, it seemed that Harris had a desire to escape the Seventh Son aesthetic, despite his love for that album. How come? At the time he gave a simple answer:

”I think some of our fans were disappointed in the musical orientation we had taken lately, so I think they’ll be happy we’re going back to a more aggressive and powerful style.”

Steve Harris

Does this mean that Harris actually took to heart the decline in American sales, and that he bought into the tendency of journalists to write off Maiden’s late 80s as “confused” and “clichéd”? It actually seems so. In which case the new album was at least a semi-conscious effort to regain their American cool. If the kids wanted more aggressive music, Maiden would be more aggressive.

Iron Maiden looking cool in 1990, optimistically wearing sunglasses to gaze into that very bright future that they hoped their No Prayer back-to-basics album and tour would bring.

As Dickinson stated in retrospect, the notion was definitely to make a kind of anti-Seventh Son album, the very sentiment that put Smith off and out of the band.

”The idea was to do something that was the opposite to Seventh Son. And the idea was to do something that was very street, very happening and something that was gonna sound good. The fact is that it sounded terrible and everybody kind of acknowledges it now … As far as production was concerned, it’s my least favourite album of all.”

Bruce Dickinson

Even Harris conceded that, ”For me, it didn’t quite come off.”

Harris claims that the new songs off No Prayer For The Dying went down really well live, but he admits to not being entirely happy with the album.

CHANGE #5 was evident as Maiden headed out on their No Prayer On The Road world tour, particularly in North America in early 1991: A clear decline in interest, smaller audiences and smaller sales. Seventh Son had nearly halved the American sales of Somewhere In Time, and No Prayer halved it again compared to Seventh Son.

The US interest in Iron Maiden was about to hit the lowest point since their 1982 breakthrough with The Number Of The Beast, only a steadily declining audience of more or less hardcore fans turning up for gigs like the Philadelphia Spectrum in early 1991:

In other words, the change of musical direction did nothing to arrest Maiden’s falling star in America, and it merely maintained the status quo in the rest of the world.

Harris would probably tell you that he never cared about sales, but wasn’t the change of style a direct response to the audience’s wishes and the journalists’ acid? Surely Maiden hoped to rectify something with No Prayer For The Dying, but failed to do so.

No Prayer On The Road for Iron Maiden and Eddie in 1990-91, the first of many tours in the 1990s that would be disappointing in light of their earlier triumphs.

It was a new decade, thrash metal was already big, with bands like Metallica and Slayer leading the charge. And the grunge wave was brewing, about to deliver a suckerpunch to the music scene with bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam and Soundgarden.

But could it not also be the case that many people simply found Maiden’s new music less interesting than the older stuff? In all honesty, does No Prayer For The Dying hold a candle to Powerslave (1984)? Was it the changing times that hurt Maiden, or did they fail to deliver the goods?

The declining fortunes of Iron Maiden were signs of things to come and their challenges had just begun. In 1990, Dickinson told Metal Hammer’s Iron Maiden special issue that, “I have the feeling as though the Nineties will be a very creative period for me.” Little did he know where that feeling would lead him.

Read on for the tale of Fear Of The Dark and Bruce Dickinson’s fateful exit from Iron Maiden!

Sources: Kerrang! issues 306 and 307 (September 1990) and issue 388 (April 1992), Metal Hammer issue 20 vol 5 (September-October 1990) and issue 8 vol 7 (August 1992), Metal Attack: Metal Hammer Special (no. 5/90), Stockholm, April 28 1996 (bookofhours.net, 1996), Run To The Hills: The Authorised Biography of Iron Maiden (Mick Wall, [1998] 2001), Classic Rock issue 33 (November 2001), The Guardian: “Rock by numbers” (Richard Adams, 31 May 2003), Kerrang!: “Maiden Heaven” (2014), Bruce Dickinson: Maiden Voyage (Joe Shooman, [2007] 2016), What Does This Button Do? (Bruce Dickinson, 2017), Classic Rock Platinum Series and Metal Hammer present “Iron Maiden” (Edited by Dave Everley, 2019), Rock Candy issue 19 (2020), Adrian Smith Interview with Raised On Radio (2020), Adrian Smith Interview with Eon Music (Eamon O’Neill, 2020), Monsters of River & Rock: My Life as Iron Maiden’s Compulsive Angler (Adrian Smith, 2020).

It’s just like a bunch of friends, that happens to be really good musicians, got together after a long time, really energized and somewhat overexcited and came up with a bunch of bad ideas (songs, recording studio, writing process etc)… It’s like you said, as soon as, Bruce and Steve agreed you’ve got 2 pretty passive members (murray, mcbrain) who are laid back and ok with almost everything, and one really unhappy camper which was Adrian … It was a losing battle, which I don’t think that Adrian was able to win.. he was the sober friend that went home early…

That’s a good analogy!

Absolutely brilliant article, man!

Agreed!

Thanks, guys! It was interesting to research this one because the chronology of events is kind of unclear in the official bio. And I think it’s important to state and restate the reasons why Adrian left, to counter the myth that he didn’t want to do heavy metal at that point. How can you call No Prayer a heavier album than Seventh Son, which is the direction Adrian wanted to stick with…?

Adrian was always the most avant-garde musician Maiden, long; Steve sailing between two waters, the classic hard rock and progressive rock of the early 70s, and Bruce follows the old school hard rock. Just listen songs like “22 Acacia Avenue” , “Flight of Icarus”, “2 Minutes to Midnight” or “Stranger in a strange land” to realize it. For me it was always clear that the reason for his departure was that Maiden did not continue in the line that had begun with “Somewhere in Time”, out of exhaustion from touring. If Adrian had not gone in 1989 Maiden possibly have done very great albums … If you think about it, It’s terrible.

I always thought that the reason Adrian Smith left was precisely the musical direction after SSOASS, besides the fatigue of touring. What would have happened if Maiden continue to SSOASS in line? Tremendous if one thinks .

”I got a phone call one afternoon from Bruce. He said, ‘Would you learn some Maiden numbers?’ The first thing I said was, ‘No,’ because we’d agreed we wouldn’t do any Maiden numbers.”

Really? Because they rocked “Flight of Icharus” and “Run To The Hills” on that TM tour…

Janick joined Maiden in January 1990, so this phone conversation was a few months before the eventual TM tour in the summer. But this is the first time I hear that they did anything Maiden other than Bring Your Daughter on that tour. Are you sure?

Absolutely, positively sure. It was one of the most treasured days of my life. I remember what they were wearing and the guy that got thrown out for starting a ruckess during a “Brucification.”

lol — Are you surprised that Bruce would change his mind?

This is the setlist for the opening night of the US tour in 1990. http://www.setlist.fm/setlist/bruce-dickinson/1990/the-bayou-washington-dc-6bdf06f6.html

It’s seems to be fairly consistent trough out. Black Night is played on some shows ++

However, I came over an interesting thing when checking the double date at the Astoria in London prior to the US tour. One of the nights claim to have The Trooper as the last encore. I have a vague memory of reading somewhere that some of the Iron Maiden members joined Bruce on stage in London and did The Trooper.

Could be a one of.

I think Bruce and his band played “Flight of Icarus” and “Run to the hills” when Adrian Smith joined to him; but in the “Tattooed Millionaire Tour” Bruce and Janick played “Bring your daugther to the slaughter” and “The Trooper”.

The Trooper? Are you sure?

Absolutely sure; 27th june 1990, in the Astoria Theatre, in London.

It was the only time they played this song in the Tattooed Millionaire Tour.

Ms. Ray, could your memory be playing tricks on you? As far as I know, the only Maiden song played by Bruce and Janick on that tour, apart from ‘Bring your daughter…to the slaughter’ (originally a solo song back then), was ‘The Trooper’ in London, as an encore with the rest of the Maiden boys.

Here is a list of bootlegs from that tour:

http://www.bookofhours.net/bdwbn/bootlist.htm#tm

And here is the information about the standard setlist:

http://www.bookofhours.net/bdwbn/toursets.htm#1990

Really? Do you think I would forget the night I spent an hour and a half enjoying the company of one of my heroes the week after my birthday? LOL! Believe me, Poughkeepsie, New York was nearly felled by the thrill in that little sardine-packed venue.

Could it be possible that they may have improvised or changed the set list? There is such thing as flexibility — it is art, you know…

Please don’t take it personally, but there is a bootleg for that show and this was the setlist that night: 😉

Intro

Riding with the angels

Born In 58

Licking the gun

Gypsy Road

Dive dive dive

Drum-solo

Zulu Lulu

Ballad of Mutt

Son of a gun

Hell on wheels

All the young dudes

Tattooed millionaire

No lies

Fog on the Tyne

Sin City

Bring your daughter to the slaughter

So much for “no Maiden.”

No, I’m not surprised about Bruce or anyone changing their mind. I had just never heard about them doing anything Maiden except Bring You Daughter on that tour. Just curious.

To be honest, I don’t think Bruce would have survived the backlash if he didn’t do *something* classic, especially in the US and at that juncture of his career. He may not have wanted to do any Maiden, but inevitably, it was a good business decision, I think. (Aside from majickal, of course!) Besides, Rod was there that night, so there may have been pressure, who knows?

Still, it seems that everything Maiden except Daughter/Slaughter was a one-off on that tour. They did a pretty good job of staying away from it, bearing in mind that they really only had about 40 minutes of music to pick from.

@Adrian: Cool, a one-off then, as Torgrim said.

So, it seems The Trooper was performed in London with the rest of Maiden, which makes sense since it was one of very few Maiden songs they had actually rehearsed with Janick at that point. (According to Steve the only other Maiden tracks Janick could play prior to rehearsals for the No Prayer tour in September 1990 where the new ones, obviously, and the rest from his audition – The Prisoner, Children Of The Damned and Iron Maiden.)

When it comes to Flight Of Icarus, could you be thinking about Bruce and Adrian in 1997, Ms. Ray, like Ghost suggests?

Should I take all these “are you sure” questions personally? Because it’s starting to get offensive, boys.

That would be taking it the wrong way. You’re simply in the company of self-confessed Maiden nerds, and it doesn’t seem anyone here has ever come across this information before, Janick performing Icarus in 1990, that’s all.

In any case this means that something is wrong with the information on that Poughkeepsie 1990 bootleg recording that Ghost linked to.

I think comments should not be taken as negative or personal. Everyone can make mistakes, and really It is a fact that Bruce just played “Flight of Icarus” and “Run to the hills” when Adrian joined him in the middle of 90s, and It`s also a fact that Bruce only made “The Trooper ” only once, in London, in 1990. From there I think the error is assumed and go.

Great research and article!

I was at the TM London gig, last night of the UK leg, where the rest of Maiden came on after the final encore to do The Trooper. The lights stayed down after the regular encore (Black Night?), and it was like an electric charge through the audience as we realised Nicko had climbed onto the drum stool. Steve and the rest walked on and they charged through The Trooper. The best bit was seeing Davey rocking out and moving like he hadn’t for years. Either Metal Hammer or Kerrang ran an interview with Jan afterwards where he said he’d have loved to play more Maiden numbers, but Trooper was the only one they’d rehearsed.

So, here are many words to the gallery.

There’s no topic about Fear Of The Dark itself yet !!!

I have one interesting question : in booklet we can see all maiden boys on the ruins of some medieval castle…where’s it? What castle?

We will get around to the Fear Of The Dark era whenever Maiden finally decide to release the Donington Live 1992 DVD. 🙂

No idea about what castle they used.

It’ll be very interesting to read about The X Factor too.

We’ll discuss all of the 1990s in critical depth at some fitting point in the future. Just thought we’d get the No Prayer era discussed this year, since it’s 25 years since Adrian left, Janick joined, and the album was made. 🙂

That’s cool! Also, 2015 is the 20th anniversary of X Factor! Give it at least some arcticle this year (now it’s almost a month to date of 20th date release!).

Nope, no time. We don’t make our living doing this, you know. 😉

Well, of course, but I see this site’s alive and quite often posting new articles news, and ect. ect… and…well, there will be NOT JUST A SINGLE(!) article about TXF for it 20th anniversary?!!!

If you want to write one, we’ll consider it for publication. 🙂

Ok, I’ll think about it. I’m the new one there… but the way you answer made me feel like TXF and whole Bayley era is unwelcome there)

Unwelcome here? Why? We don’t have to like something to write about it, Maiden Revelations is about all things Maiden. When it comes to these in-depth features about Maiden history, we just started at the beginning, in this feature, and we’ll keep going forward at the right occasions. Don’t have time for everything.

But we’ll certainly take a shorter piece for the TFX anniversary, if you have one. How about you write something about how and why you love the album? 🙂

Thanks a lot for all the infos your website is incredible !

The seventh son album was the finale for maiden. They should have ended their journey.

But you’re still here, 27 years later…

27 years later still rocking to the 7 wonderful albums they gave us. Iron Maiden ruled the 80’s. long live the 80’s!

Hi Chris,

I kind of agree with you, I quit listening to them after Powerslave.

Then, one day, I saw a video about Blaze’s day on youtube, and heard the chorus of Man on The Edge.

I was like “hey, this seems to be good”

Went on to listen to X Factor and Virtual XI and fell in love with both, it is not good, it is EXCELLENT

So many GREAT songs, Iron Maiden had finally found their way back to making GREAT music. Even the drumming of Nicko, which for me killed the real Iron Maiden, sounds better.

But then, Bruce came back and with him the same old thing we got tired of. I try, I really try, I try real hard to listen to their stuff after Powerslave and 95% of the times I can’t even finish the song. Afraid to Shoot Strangers being the exception.

Maybe Christer can list some songs from the other 1988-> albuns we should give a try.

Cheers,

Marcelo.

i love no prayer for the dying. to me the only bad songs are assassin and hooks in you. everything is awesome. mother russia a little less awesome but still good

i meant everything else*

This is the best summary I have read of Adrian’s departure and the events leading up to NPFTD. I must admit to being fascinated by this whole period of the band’s history.

As a massive Adrian fan, I would have loved to have heard Maiden continue in the same direction as SIT and SSOASS (one of the great lost opportunities) but I have to admit at the time – as a 17yo – I was one of the many who thought Maiden should go back to sounding more ‘heavy’. I was excited, but ultimately disappointed, to hear NPFTD which I thought sounded tired and a bit ‘clanky’ – even the cover artwork seemed basic. I liked Tailgunner, but found Bring Your Daughter.. (apart from the cool chord change in the verse) to be a little basic and was embarrassed that this song was their only number one. But then again I had also been a little thrown by Can I Play With Madness? a couple years back when I first heard (and taped it) on Tommy Vance’s Friday Rock Show, although I loved the album.

In retrospect, with the rise of grunge, predominance of thrash and other changes in the wider musical world, it was inevitable that the Maiden empire-period ended with SSOASS. Certainly – despite some great music since – the ‘magic’ of that period has never been recaptured… on record, at least.

Thank you for reading the piece and sharing your thoughts, Ed.

Thanks again for a wonderful, well researched article. I really hope Adrian does a proper autobiography at some point about his time in Maiden. The details that have emerged are quite tantalising! I wonder if Steve has any demos of the No Prayer material with Adrian kicking around somewhere? Based on your well researched timeline it seems like he might have demoed 4 or 5 tracks that are mentioned during the early writing sessions? As you’ve said a few times Maiden are well overdue a set of deluxe remasters with all of this stuff included 😉

Thanks, stevenwall! Actually, Steve has said that they recorded at least The Assassin before Adrian left. Being pre-digital I’m not sure it would have been kept when Janick replaced the guitars, but what a find that would have been for a future box set.